WHICH WAY, WHICH WAY?, 1956

CHARLES BLACKMAN

tempera and oil on composition board

122.0 x 121.5 cm

signed and dated upper left: BLACKMAN 56

Barbara Blackman, Melbourne, a gift from the artist in 1957

Private collection, Melbourne, acquired in April 1987

Probably: Paintings from Alice in Wonderland, Gallery of Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 12 – 22 February 1957

‘Alice in Wonderland’ by Charles Blackman, Johnstone Gallery, Brisbane, 4 – 21 September 1966, cat. 17

‘Alice in Wonderland’ by Charles Blackman, South Yarra Gallery, Melbourne, 21 – 30 March 1967, cat. 26

Charles Blackman ‘Alice in Wonderland’, David Jones’ Art Gallery, Sydney, 14 – 26 October 1968, cat. 31

‘Alice in Wonderland’ painted in 1956 – 57 by Charles Blackman, Heide Park and Art Gallery, Melbourne, 24 May – 10 July 1983, cat. 28

Charles Blackman: Alice in Wonderland, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 11 August – 15 October 2006, cat. 4

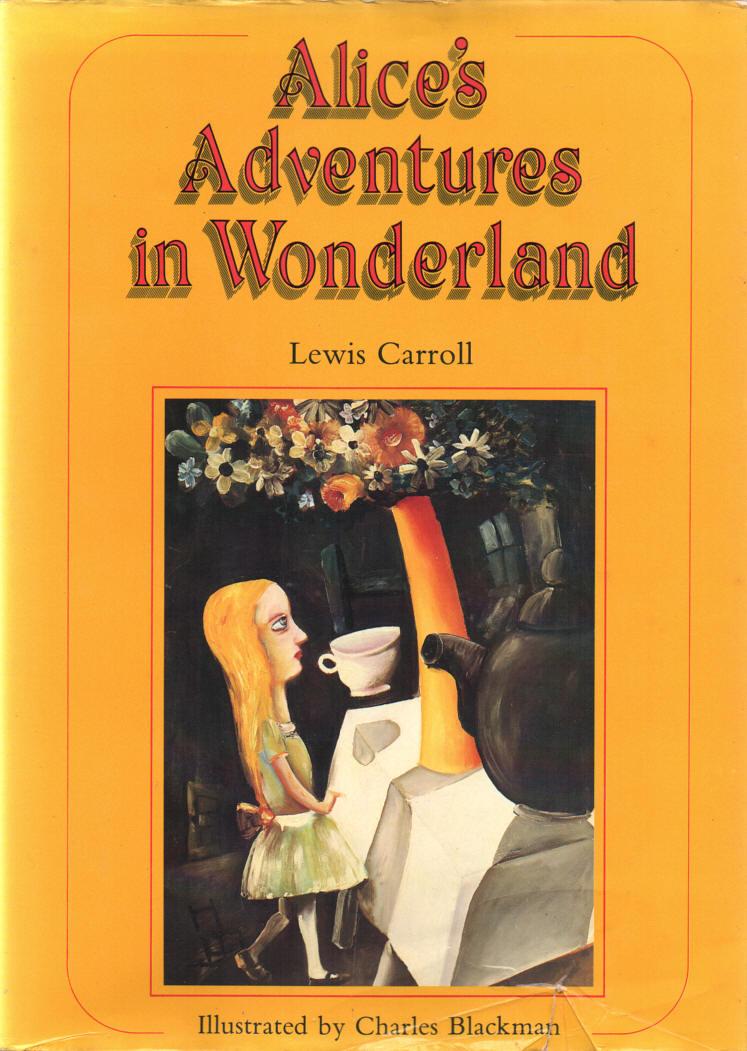

Carroll, L., Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: Illustrated by Charles Blackman, A.H. & A.W. Reed, Sydney, 1982, p. 22 (illus.)

Moore, F. St. J., and Smith, G., Charles Blackman: Alice in Wonderland, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2006, pp. 17, 46, 47 (illus.), 134

84550.jpg

| Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, Illustrated by Charles Blackman, A.H. & A.W. Reed, Sydney, 1982 |

We are grateful to Felicity St John Moore for kindly allowing us to reproduce the following excerpts from her essay ‘Conception to Birth: The Alice in Wonderland Series’ and catalogue entry for the present work, in St John Moore, F. & Smith, G., Charles Blackman, Alice in Wonderland, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2006, pp. 10 – 18, 46

Alice’s adventures began as an improvised tale told to ten-year-old Alice Liddell and her sisters, daughters of the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, during a boat trip on 4 July 1862. The rest has become part of our heritage. Lewis Carroll, as the pseudonym of the gentle mathematician Charles Dodgson, published the illustrated book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865, and it became a classic of children’s literature. Then, in 1871, he published a sequel, also illustrated, Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There.

Charles Blackman grew up in a family without books. The first time he heard Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was on a talking book borrowed from the library for the blind in 1956 by his wife Barbara, a writer who had been legally blind since 1950. He therefore experienced the book without the illustrations. ‘I’d never read Alice in Wonderland, although I’d heard of it of course. And I’d never seen Tenniel’s drawings, which are very famous illustrations to this magnificent and marvelous book, which everyone’s analysing out of their minds eternally. And it means so much to everybody, including me.’1

Blackman #3.jpg

| Installation view of the Charles Blackman exhibition Alice in Wonderland, Johnstone Gallery, Brisbane, 4-21 September 1966 photographer: Arthur Davenport courtesy of James Hardie Library of Australian Fine Arts, State Library of Queensland, Brisbane |

The recording was beautifully read by Robin Holmes, a BBC announcer. Blackman was twenty-eight, a painter of adolescence and the feminine psyche. In love with symbolist literature, the poetic image, surrealism and Barbara, for Blackman the book was a doorway to his own myth.

Listening to the story again and again, he was struck by the parallels with his own life – not just the feeling that anything could happen but that everything was happening, all at once! As he put to Robert Peach:

‘I was absolutely thrilled to bits with it… and it seemed to sum up for me at that particular moment my feelings towards surrealism, and that anything could happen. The cup could lift off the table by itself, the teapot would… pour its own tea… when [Alice] passes through the mirror. The world is a magical and very possible place for all one’s dreams and feelings. One is completely outside of reality… This was sparked completely off by Barbara’s influence on my life.’2

Black #4.jpg

| Charles Blackman Goodbye Feet, 1956 tempera and oil on composition board, 116.0 x 122.0 cm National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © Charles Blackman/Copyright Agency, 2024 |

Blackman #5.jpg

| Charles Blackman Alice, 1956 tempera and oil on composition board 133.0 x 90.0 cm Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne © Charles Blackman/Copyright Agency, 2024 |

Above all, Blackman was struck by the parallel between the fabulous Alice and the familiar Barbara, including her increasing sense of spatial disorientation to which they were both then adjusting. In Barbara’s words, ‘Alice was moving enquiringly, questioningly, trustfully, bemusedly, changefully, into a new and strange world, trying with good sense and honesty to get her bearings in it, however often she seemed to change body shape and whereabouts.’3 For Barbara, these changes in body shape were caused, as it happens, by her first pregnancy, a joyous event which was to coincide with the start of the series proper and lasted the nine-month duration of its making. This pregnancy, which transformed Barbara’s innocence into womanhood, in parallel with Alice’s transformation from dream to reality, became a key to the shaping and evolution of the series.

Pregnancy also had a side effect, ending her work as a life model (thereby impelling the finding of another model for John Brack’s series of nudes), and cutting the earnings that had supplemented her blind pension as their income, allowing Charles the chance to paint full-time. So Charles spent regular time at the Eastbourne Café in Wellington Parade, Melbourne, where he was employed as a short-order chef for his friend Georges Mora and was actually involved with chairs, tables, dishes and people, the paraphernalia of the Alice series. The restaurant came into the paintings:

‘It used to be referred to as the kitchen ballet. I used to leap from fridge to plate… my record was serving a hundred and four meals, three courses, absolutely fully served, of – not haute cuisine, but not bad food – in under two hours [for a French film crew who came out in advance of the Olympic Games]. You could work it out minute by minute for yourself.’4

Blackman #6.jpg

| Charles Blackman The Blue Alice, 1956-57 tempera, oil and household enamel on composition board 122.0 x 122.0 cm Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane © Charles Blackman/Copyright Agency, 2024 |

Charles came home after his nightly cooking in the restaurant with his head full of spinning plates and teacups; Barbara would say he brought the rabbit into the restaurant at night, and it would help him do the work, and the next day he would paint it all.’5

…The concept of an Alice in Wonderland series was born at the opening of Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly series (1946 – 47) exhibition in the new Gallery of Contemporary Art in Melbourne in late June 1956; there began the pregnancies. With the Alice paintings already underway and their personal relevance multiplying by the minute, the concept of the series blossomed. Firstly, the Ned Kelly paintings were literary, based on the vernacular in captions and jingles, but not illustrative. Secondly, they were also personal, as was known within the walls at the time, relevant to Nolan’s ménage à trois with Sunday and John Reed.

In the same way, the Blackmans had identified their own surreal adventures with the Alice story and Charles would use the series to evoke his personal poetic image. The expressive figure of Alice, as Barbara, is ever present; so (usually) is the White Rabbit, as the artist, Charles, there by implication when not visible. So again is the bouquet, a symbol of creation and carnality, the flowers in the centre of the table as though for a birthday.6 Then, there is the teapot, a pre-maternal shape with different personalities and roles; the magic bottle, or bottle of change, usually tipping/tilting on the shady side of the picture space; and of course, the white tablecloth with its handy apron, at once a versatile motif and a pictorial device.

Black #7.jpg

| Charles Blackman Alice closing up like a telescope, 1956 tempera and oil on composition board 135.9 x 121.0 cm Private collection © Charles Blackman/Copyright Agency, 2024 |

Blackman #8.jpg

| Charles Blackman The flowers growing, 1956 oil and tempera on composition board 134.6 x 97.0 cm Private collection © Charles Blackman/Copyright Agency, 2024 |

* * * * * *

‘Oh my poor little feet, I wonder who will put on your shoes and stockings for you now, dears? I’m sure I shan’’t be able! I shall be a great deal too far off to trouble myself about you: you must manage the best way you can – but I must be kind to them,’ thought Alice, ‘or perhaps they won’t walk the way I want to go!’7

In this surprising composition, Blackman links Alice’s sense of separation from her body to the threat of separation facing the real Alice (Barbara) and the White Rabbit (Charles) as a result of her pregnancy. Their predicament was an artistic one, the question of whether the White Rabbit should go or stay: choose the path of artistic freedom on the basis that ‘artists don’t need wives’ (as Sunday Reed advised), or stay with his wife and muse, the pregnant Barbara. Cosmus or domus, that was the question. This painting is in the manner of a poetic portrait of the dilemma.

The room itself appears to be both illogical and in a state of becoming, expressing correspondences between the inner and outer, image and colour. The side walls double as changeful skies that stretch back into the corners of a full wall of wildflowers, tunnel-like, under a cloudy, charcoal-grey roof. The floor is in a similar state of becoming, as though illuminated from below, or blue shadows. These dream-like images impart the idea of poetry, transience and uncertainty. So does the childish table, its flask rocking, fore legs washed with pink. On the right, the transforming wainscot leads to the stars through the sunset panels of the door, to the night sky below and outside.

Blackman and Christabel_1968_ David Jones Galley.jpg

| Charles and Christabel Blackman at Charles Blackman: Alice in Wonderland, David Jones Art Gallery, Sydney, 14 – 26 September 1968 photographer unknown courtesy of Charles Blackman papers |

In one direction, this open door points to the sky and twinkling of the friendly stars, implying artistic freedom. In the other, the low diagonal perspective leads back to the skirts of domesticity through the growing figure of Alice. Her moon-like face shines in a golden-haired alcove, above the blue-belling of her skirt. From the depths of her twinkling hem, her ‘bloomering’ eyes peer down her long flamingo legs as the White Rabbit heads back from the night. Notably, his urgent image is dualistic8, with two profiles – at once man and beast – his instinctive leap akin to an act of faith. That this is the way of the future is implied by his igniting (with a twist of his extended ear) the visionary bouquet, its skinny vase springing from the centre of the fertile floor. In company with the still-perfumed imagery of earlier creations, such as the shy bouquet over the rose-lipped vase, this newborn and imaginative creation suggests that there are always alternatives. As the White Rabbit can see through the arch of Alice’s legs, left is right and right is left, and her socks are tweedling this way and that.

Both ways lead in the same direction. It doesn’t matter which way – ‘they’re both mad.’9

1. Charles Blackman, interview with Robert Peach, Sunday Night Radio Two, ABC Radio, 9 September 1973

2. Charles Blackman, ibid.

3. Barbara Blackman, cited in St John Moore, F., Charles Blackman: Schoolgirls and Angels: A Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1993, p.4

4. Charles Blackman, op. cit.

5. Charles Blackman, cited in Shapcott, T., The Art of Charles Blackman, Andre Deutsch, London, 1989, p. 13

6. See Freud, S., The Interpretation of Dreams, Macmillan, New York, 1932, p. 374

7. ‘The Pool of Tears’ in Carroll, L., Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Macmillan, London, 1974, pp. 16 – 17

8. That this image evolved during the creative process is evident from a pair of sideways ears, overpainted by the artist, their buried outline visible in the raking light.

9. Carroll, op. cit., p. 97

FELICITY ST JOHN MOORE