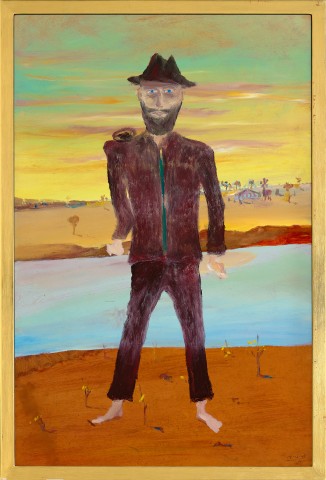

STURT ON THE RIVER BANK, 1948

SIDNEY NOLAN

Ripolin enamel on composition board

90.0 x 60.5 cm

signed with initial and dated lower right: N 15–4–48

Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne

Lord Alistair McAlpine of West Green, United Kingdom, November 1986

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, a gift from the above in 1995 (label attached verso)

Sotheby’s, Sydney, 26 November 2007, lot 28

Private collection, Western Australia

Michael Reid Galleries at Sydney Contemporary 2024, Carriageworks, Sydney, 5 – 8 September 2024

Morse, J., ‘The Short–Sighted Explorer’, Link, April 1999, pp. 16 – 17

‘Nolan works fetch more than $700k’, ABC News, 26 November 2007,

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2007–11–26/nolan–works–fetch–more–than–700k/969332?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web (accessed March 2025)

130815-(cleaned up).jpg

Sturt on the riverbank, 1948, was painted shortly after a turbulent year for Sidney Nolan during which he completed his famed ‘Ned Kelly’ series before escaping the hothouse intrigues of Heide and marrying Cynthia Reed. As ‘survivors’ of Heide, Nolan and Reed ‘knew each other’s baggage. Cynthia gave Nolan an intelligent companion, an agile front-row forward for his career… He also achieved a settled home life (whilst) Cynthia gained a partner and a cause. Above all, they considered each other intellectual equals, respecting and supporting their separate work habits.’1 The couple were married on 25 March 1948, and Sturt on the riverbank was painted three weeks later.

Nolan famously claimed that the original Kelly series was ‘secretly about myself… From 1945 to 1947 there were emotional and complicated events in my own life. It’s an inner history of my own emotions’2; and he is also recorded as saying that Sturt on the riverbank was another psychic self-portrait. Nolan’s great hero was an additional dreamer, the French poet and explorer Arthur Rimbaud who similarly furthered his posed identity as an outsider. Nolan’s choice of comparable individuals as subjects for his paintings furthered this image. These included the ship-wrecked Eliza Fraser, a saga of survival, betrayal and hopeless dreams; the bleakly doomed Burke and Wills; and Captain Charles Sturt who fervently believed that Australia possessed an inland sea. These names, like Kelly, now have a mythic quality in this country’s colonial history, particularly the British-born explorers who pitted themselves against the hostile interior, a ’testing ground for men and the repository of stern virtues.’3 Sturt was so obsessed by his idea that he undertook three separate expeditions, the first of which identified the junction of the Murray and Darling rivers whilst encountering numerous stable villages and many hundreds of indigenous Yorta-Yorta (hardly terra nullius). The third expedition almost killed him as they crossed the Stony Desert before being halted by the endless sand expanses of the Simpson Desert. Nearly blind, Sturt finally accepted that an inland sea was folly and returned a broken man.

nolan-(cleaned).jpg

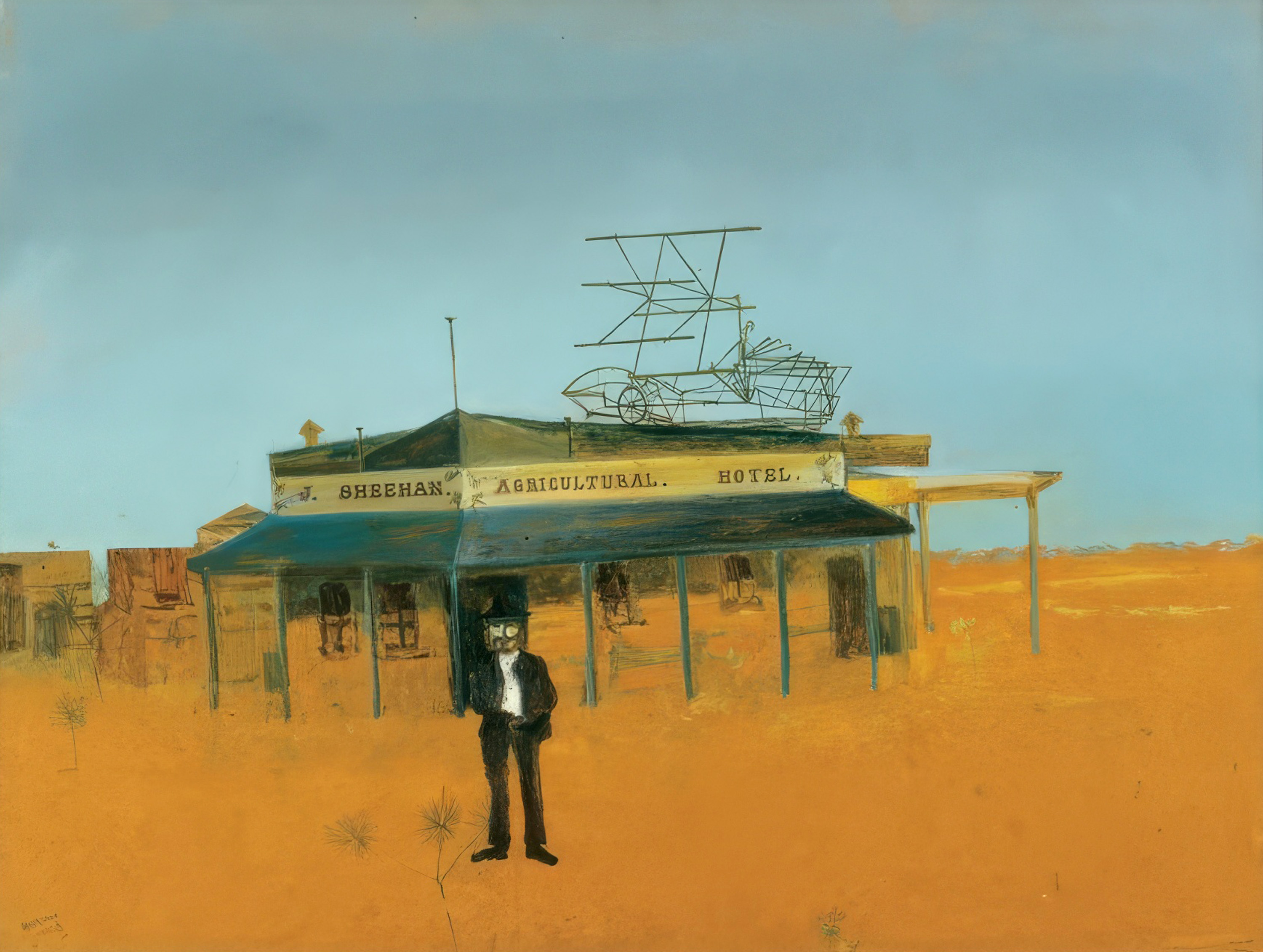

This culture clash of hapless Europeans in Australia informs Nolan’s depictions of his characters. In the Kelly series, for example, Nolan is hardly flattering to the dignity of the hapless, English troopers bashing around the bush as they track the elusive outlaws whilst Kelly, equally comical, is depicted as ‘the invincible and immortal hero of the puppet show; Australia’s Petruska.’4 Likewise, the explorer’s eyes in Burke, 1950 (private collection) burn with a fanaticism bordering on insanity, before he and Wills fuse in later paintings into spectral figures atop their camels. In Sturt on the riverbank, the explorer poses awkwardly having turned his back on the small homestead in the far distance and crossed his river of no return. Sturt is bearded, barefoot despite his suit, and wears a skew-whiff hat that seems to be too small for his head. Noting Nolan’s comment that the Kellys were painted with ‘Rousseau and sunlight’5, the poet Robert Melville wrote that like other European naïve painters, Nolan’s figures are ‘stiff, solemn, incorrect versions of the human figure oddly and intensely imbued with human presence. Their heads are slightly too large for their bodies, and the narrow part of their bodies tends to dwindle… Their faces are expressionless. Their movements stiff and doll-like.’6 This looming frontal engagement with the figure is one Nolan had employed to great effect earlier in Footballer, 1946 (National Gallery of Victoria); and Marriage of Aaron Sherritt, 1947 (National Gallery of Australia).

Painted in Nolan’s favoured medium of Ripolin enamel, Sturt’s piercing blue eyes reflect a sunset-streaked sky which echoes that seen in The encounter, 1946 (National Gallery of Australia). The homestead is uncannily similar to Nolan’s depiction of the Heide cottage seen behind the figure of Sunday Reed in Rosa mutabilis, 1945 (Heide Museum of Modern Art) and these elements allude to the possibility of the self-portrait, with the river being the Rubicon that Nolan has now also crossed. Notwithstanding, there is no known evidence that the painting had an alternate name when owned by Nolan’s friend and patron Lord Alistair McAlpine; and it was titled Sturt on the riverbank for the twelve years that it was owned by the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Supporting this appellation, moreover, is the companion painting On the Murray, 1948 (University of Western Australia) which depicts a similarly attired Sturt squatting by a riverboat.

1. Underhill, N, Sidney Nolan: a life, Newsouth, Sydney, 2015, pp. 198 – 199

2. Sidney Nolan, cited in Underhill, N. (ed.), Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his own words, Viking, Victoria, 2007, p. 268

3. Lynn, E., Sidney Nolan: myth and imagery, Macmillan, Melbourne, 1967, p. 20

4. Melville, R., Ned Kelly, Thames and Hudson, London, 1964, p. 1

5. Clark, K. et al, Sidney Nolan, Thames and Hudson, London, 1961, p. 30

6. Melville, op. cit., p. 3

ANDREW GAYNOR