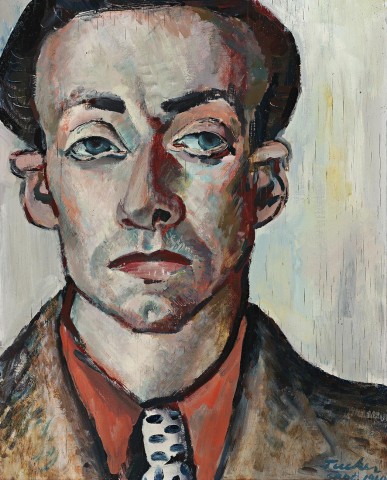

SELF PORTRAIT, 1940

ALBERT TUCKER

oil on plywood

37.5 x 30.5 cm

signed and dated lower right: Tucker / Sept 1940

Dr Guy Reynolds, Melbourne

Thence by descent

Mrs B. Newsome (née Mary Reynolds), Melbourne

Deutscher~Menzies, Melbourne, 8 September 2004, lot 44

Private collection, Sydney

Art in Australia, Third Series, Sydney, March – May 1941, p. 95 (illus.)

Uhl, C., Albert Tucker, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1969, cat. 2.11, pp. 12, 93, (illus.)

Burke. J., Australian Gothic: A Life of Albert Tucker, Knopf, Random House, Sydney, 2002, p. 167

Self Portrait, 1937, oil on paperboard mounted on composition board, 56.4 x 42.8 cm, in the collection of National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Self Portrait, 1939, oil on board, 51.8 x 42.8 cm, in the collection of Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne

Self Portrait, 1945, oil on gauze on cardboard, 75.5 x 60.5 cm, in the collection of National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

The incisive vision that Albert Tucker brought to his images of life in Melbourne during wartime was also applied to the portraits of friends and other subjects he produced during these years, as well as a group of striking self portraits. In an interview with fellow artist James Gleeson in 1979 however, Tucker described the challenges of describing one’s own appearance in visual form, saying ‘Yes, it is very hard dealing with one’s own image. I am experiencing this right now. Every now and then I look in the mirror and I realise that I am quite different now to what I was then. I am beginning to feel that testing thing, where I would like to do a … run of self-portraits … One gets trapped in a curious delusional state with one’s own image’.1

Tucker painted two self portraits in 1937 – one now in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra and a second, since lost. Exhibited at the Victorian Artists’ Society autumn exhibition that year, the latter caught the eye of Herald art critic Basil Burdett who described it as ‘turbulent and romantic’, as well as ‘forceful and waywardly individual’.2 Tucker’s self portraits at the time were created in his bedroom which doubled as a studio, and painting his face reflected in a mirror, he recalled that he was both a cheap and accessible model.3 Still in his early twenties and finding his way in the world, as well as establishing his own artistic voice and place within the art world, Tucker expressed a youthful search for self-understanding and identity in his early self portraits. Combined with his innate ability to penetrate the surface of the subject, this resulted in a series of powerful images that as Janine Burke notes, chart Tucker as ‘confrontational, haunted and passionately self-conscious’ in 1937 and just two years later, as exemplified by a self-portrait held by Heide Museum of Modern Art, show him transformed, ‘an accomplished modernist portraitist … confident and handsome.’4

Self portrait, 1940 presents Tucker without the swagger of the earlier Heide work but his confidence, both as an independent man and, more importantly, as an artist, remains strongly evident. While his pose is frontal and direct, his eyes look off to the side – perhaps as a consequence of working from a mirror – and lend the work a gentle, contemplative character which is reinforced by the delicate painterly treatment of its surface. Heavy lidded eyes, curiously shaped ears and a distinctive bent nose record Tucker’s appearance which is familiar to us from other such images and the photographic self-portraits he made after acquiring a second-hand camera in 1940. This painting was originally owned by Dr Guy Reynolds, a psychologist and lay member of the Contemporary Art Society, who along with John Reed had responded to the artist’s entrepreneurial proposal that they pay him a weekly stipend that would allow him to focus on his art. After six months they selected a painting that had essentially been paid for in weekly instalments. Reynolds also bought Urban Landscape, 1938 (private collection) in this way and later Tucker painted both his portrait and that of his daughter Mary.5

1. Tucker, A., interviewed by Gleeson, J., 2 May 1979, National Gallery of Australia Research Library, https://nga.gov.au/Research/Gleeson/pdf/Tucker.pdf, accessed 18 July 2018, p. 6

2. Burdett, B. quoted in Burke, J., Australian Gothic: A Life of Albert Tucker, Vintage, North Sydney, 2003, p. 43

3. Tucker, op. cit., p. 2

4. Burke, J., op. cit., pp. 43, 116

5. ibid., p. 167. Portrait of Mary Reynolds, 1942 is in a private collection and the portrait of Dr Guy Reynolds is now lost.

KIRSTY GRANT