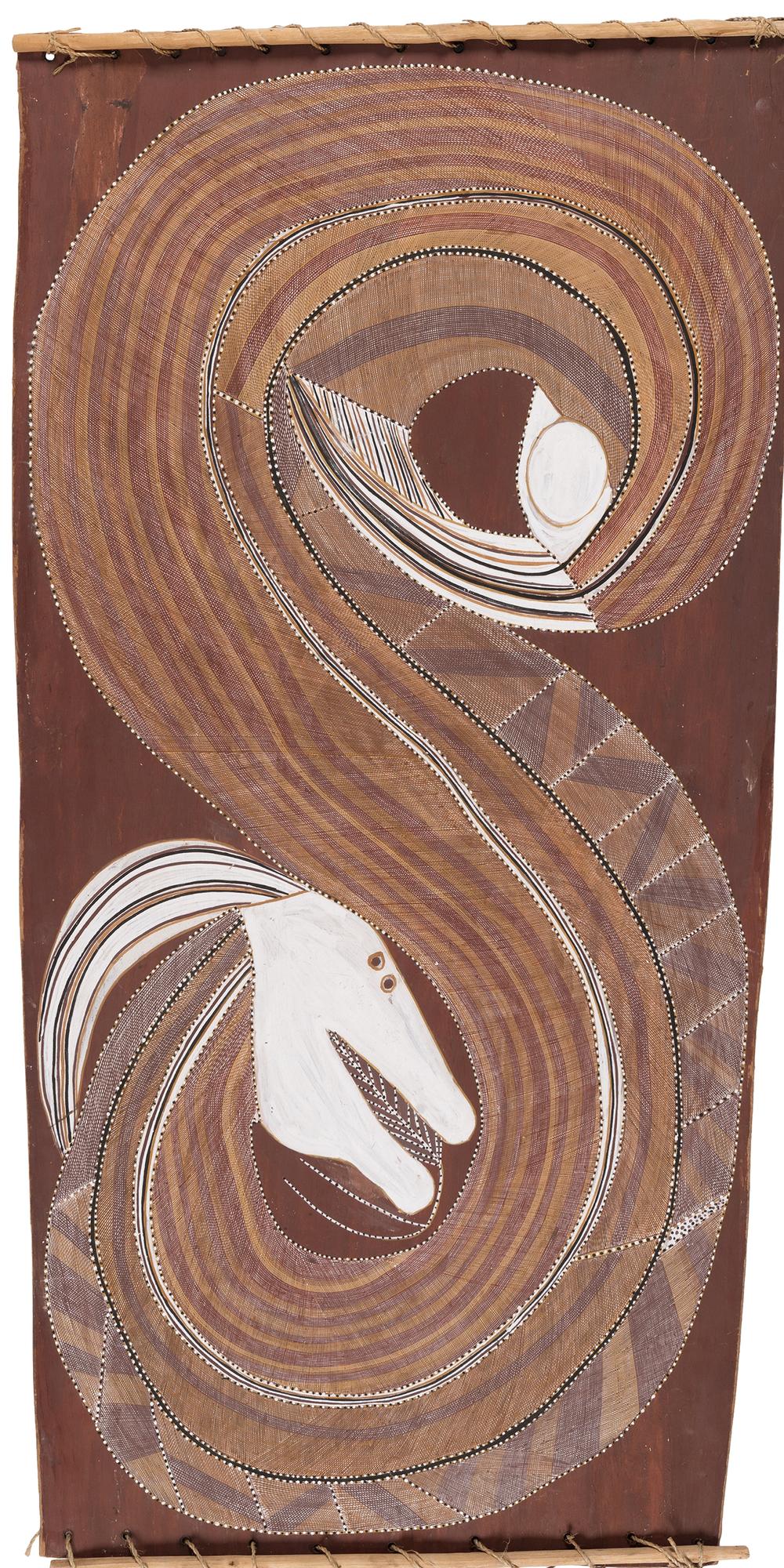

NGALYOD, 1993

BALANG NAKURULK (MR MAWURNDJUL)

natural earth pigments on eucalyptus tetradonta bark

198.0 x 66.0 cm (irregular)

bears inscription on label verso: artist's name, medium, language group and Maningrida Arts and Culture cat. 1233

Maningrida Arts and Culture, Maningrida, Northern Territory

Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne (label attached verso)

Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in December 2007

John Mawurndjul, Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi in association with Maningrida Arts and Culture, Melbourne, 20 November – 22 December 2007

Kohen, A., Taylor, L., and Altman, J., John Mawurndjul, Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne, 2007, p. 31 (illus.)

‘My head is full up with ideas.’1

c9a890df322cfbb6b4fc651c1b975a84.jpg

Original and uniquely Australian, the art of Balang Nakurulk (Mr Mawurndjul) was the culmination of decades of learning and the fine-tuning of his craft over time, resulting in a distinct record of country and an individual style of storytelling subtly contained within his intricate and beautiful paintings on bark.

Since he first began painting in the late 1970s, Balang quietly transformed Kuningku bark painting. His early works of figures and creatures in Kuningku mythology evolved into a more metaphysical representation of specific sites, events and landscapes that serve as a link between the spiritual and human worlds. Nowhere is this evolution more evident than in his renditions of Ngalyod, The Rainbow Serpent – an omnipotent and significant creature in Kuninjku cosmology associated with the creation of all sacred sites, djang, in Kuninjku clan lands.

‘I always thought about Ngalyod and how to paint it… In [early] pictures, I use dot infill like the old people, but now I have changed, I have my own style, my own ideas, you don’t see dot infill anymore… I went and painted bigger barks… Ngalyod is very powerful and dangerous... I paint her from my thoughts.’2

Ngalyod appears as a subject in his early paintings but as Balang’s knowledge grows through the guidance of his late elder brother, Jimmy Njiminjuma, and his participation in ritual ceremonies, his work reflects the more transformative power of Ngalyod. His paintings become representative of the destructive potential of this being and ‘many of his works, particularly the Ngalyod paintings, act as definitive warnings to family, friends and visitors alike, illustrating the vengeful capacity of beings to punish transgressors or those who do not have ritual authority.’3

‘Rainbow Serpents are found in many places in both dua and yirridjdja moiety. They live in the earth under the ground or in bodies of water at places such as Dilebang or Benedjangngarlwend. The white clay in the ground at Kudjarnngal is the faces of the serpent. Waterlilies at certain places tell us that the Rainbow Serpent lives there. When the wet season storms come, we can see her in the sky (as a Rainbow). She makes the rain. When the floodwaters of the wet season rise, we say the Rainbow Serpent is making the electrical storms of the monsoon wet season. Rainbow Serpents are dangerous, just like crocodiles, they can kill people and other animals.’4

dh200361.jpg

As Mawurndjul relates above, Ngalyod resides in the waterholes and water courses. Waterlilies growing around their edges may indicate the presence of Ngalyod and Kuninjku are careful not to damage the lilies or disturb the still bodies of water so as not to anger the spirit. The power of Ngalyod is evident in this early version from 1993 which features the profile of the Serpent’s head clearly distinguished in vivid white clay to the top of the bark, while its powerful curling body pushes out to the borders of the bark support covered with shimmering fields of ochre rarrk extending to the corners. Creatures and plants from the waterhole are pushed to the bottom of the composition, and energy radiates from the painting – indicating the potential power within that is both life-giving and rejuvenating, and, at the same time, destructive.

Balang’s paintings have pioneered a new interpretation of Kuningku clan sites and djang that inspire the next generation of bark painters. Constantly striving for new ways to interpret country, his innovative use of rarrk to map important locations is evident in the fine lineal clan designs spread across the surface of his paintings, creating shifting patterns of grids that are rendered in fine interlocking lines. As Hetti Perkins writes ‘His works, lovingly crafted and sculpted depictions of flora and fauna, ancestral events, supernatural beings, significant sites and encrypted ceremonial designs are at once country and mnemonic of country.’5

Balang’s art is universally celebrated and accordingly, has been included in many seminal exhibitions at major galleries and museums, both within Australia and abroad, including: Dreamings, New York (1988); Crossroads, Japan (1992); and Aratjara: Art of the first Australians, Germany and England (1993 – 94). ln 2000, his work was featured at the Sydney Biennale and in 2004, twenty-two of Balang’s works were curated by Hetti Perkins in Crossing Country at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Significantly, Balang has also been honoured with two major retrospective exhibitions of his work: rarrk – John Mawurndjul: Journey Through Time in Northern Australia at the Musee Jean Tinguely, Basel, Switzerland in 2005, and John Mawurndjul, I am the Old and the New, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney in 2018. The recipient of four Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, and the winner of the prestigious Clemenger Prize at the National Gallery of Victoria in in 2003, Balang was awarded an Order of Australia in 2010 ‘for service to the preservation of Aboriginal culture as the foremost exponent of the Rarrk visual art style.’6

1. Mawurndjul, cited in John Mawurndjul, I am the Old and the New, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 2018, p. 336

2. Mawurndjul, Interview with Apolline Kohen, cited in Kaufmann, C., et al., rarrk – John Mawurndjul: Journey Through Time in Northern Australia, Crawford House Publishing Australia, Belair, South Australia, 2005, pp. 25 – 26

3. Perkins H., ‘Mardayin Maestro’ in John Mawurndjul, I am the Old and the New, op. cit., p. 26

4. Mawurndjul, cited in John Mawurndjul, ibid., p. 200

5. Perkins, op. cit., p. 21

6. https://honours.pmc.gov.au/honours/search?searchText=john%20Mawurndjul (accessed 15 February 2025)

CRISPIN GUTTERIDGE