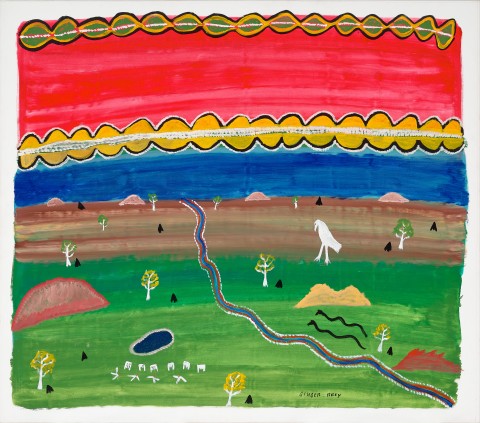

NGAK NGAK AND LIMMEN BIGHT COUNTRY, 1994

GINGER RILEY MUNDUWALAWALA

synthetic polymer paint on cotton duck

130.0 x 147.5 cm

signed lower right centre: GINGER RILEY

bears inscription verso: Alcaston Gallery cat. AK2433

Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne (stamped verso)

Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in July 1995

Ginger Riley Munduwalawala – ‘you can see for long way', Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne, 4 – 25 August 1995

This work is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity from Alcaston Gallery which states:

'This painting depicts Ngak Ngak and Limmen Bight country.

Ginger Riley Munduwalawala believes he is a direct descendant of the first man and that the world as he knows it commenced at the Four Arches. His position in his known world is confirmed by ancestral myths and legends which illustrate Munduwalawala's lineal connection and ritual title to his mother's country - the land around the Four Arches which are hills near the mouth of the Limmen Bight River in South East Arnhemland.

The Four Arches were formed by the snake Bandian. This snake, a king brown snake, appears in various guises, sometimes as two snakes, is known as Garimala or Kurra Murra and undergoing transformation becomes Wawalu, the Rainbow Serpent.

The sea eagle Ngak Ngak is often shown singly or as a repeated image; he acts as a sentinel looking around Munduwalawala's mother's country.

The image illustrates land marks, rocks, hills, islands and caves.

Munduwalawala believes his country is inhabited by totemic beings in the form of snakes, birds and ancestral people. Past and present integrate. The ceremonies as they are performed and explained establish his kinship and country.

Munduwalawala treats his totems, in the western sense, as heraldic devices. His stories are his, but the written interpretation is ours. He holds copyright over his images - his cultural property. The story written is not his.'

‘My mother’s country is in my mind.’1

Distinguished by their daring palette, dynamic energy and strongly flattened forms, Riley’s bold, brilliantly coloured depictions celebrating the landscape and mythology of his mother’s country are admired among the finest in contemporary Indigenous art. Emerging at a time when barks were the familiar output for his Arnhem Land country and Papunya Tula paintings were considered the norm, his striking interpretations challenged preconceived notions of Indigenous art – thus earning him the moniker ‘the boss of colour’ by artist David Larwill. Notably influential upon such idiom was Riley’s chance encounter during his adolescence with celebrated watercolourist Albert Namatjira, whose non-traditional aesthetic and concept of ‘colour country’ left an indelible impression upon the young artist. Encouraged by ‘…the idea that the colours of the land as seen in his imagination could be captured in art with munanga (white fella) paints’.2 Nearly three decades passed before Riley would have the opportunity to fully explore his talent when he attended a printmaking workshop at the Northern Territory Open College of TAFE in Ngukurr. At the mature age of 50, Riley rapidly developed his own sophisticated style and distinct iconography and, after initially exhibiting with Ngukurr-based painters, he soon established an independent career at Alcaston Gallery. Enjoying tremendous success both locally and abroad over the following sixteen years before his untimely death in 2002, Riley received a plethora of awards and in 1997, was the first living indigenous artist to be honoured with a retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Capturing the saltwater area extending from the coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria along the Limmen Bight River to the weather-worn rocky outcrops known as the ‘Four Archers’, Ngak Ngak and Limmen Bight Country, 1994 offers a stunning example of Riley’s heroic landscapes. Pivotal to the composition is the totemic, white-breasted sea eagle, Ngak Ngak, who presides over the landscape. Weaving its way through the centre of the composition, the Limmen Bight River appears as an intense blue undulating ribbon, offering not only a dramatic visual accent but poignantly anchoring the work to the artist’s mother country. Meanwhile, Garimala, the mythological Taipan who, according to the ancestral dreaming, created the Four Archers – an area regarded as ‘…the centre of the earth, where all things start and finish’3 – is depicted as a pair of black snakes (a typical convention to denote him travelling). Informed by the artist’s strong sense of place, the aerial perspective sees the Four Archers envisaged in multiple to both emphasise their significance and reflect different viewpoints; as Riley observes, he often paints ‘…on a cloud, on top of the world looking down… In my mind, I have to go up to the top and look down to see where I’ve come from, not very easy for somebody else, but all right for me. I just think in my mind and paint from top to bottom, I like that’.4

A vibrant celebration of the joy of belonging to the saltwater country of the Mara people, indeed the work embodies Riley’s powerful vision of his mother’s country as a mythic space – a mindscape whose kaleidoscope of dazzling colours and icons continually evoke wonder and mystery in the viewer with each new encounter.

1. Riley, cited in Ryan, J., Ginger Riley, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1997, p. 15

2. Riley, cited ibid.

3. Riley, ibid., p. 29

4. Riley, ibid., p. 27

VERONICA ANGELATOS