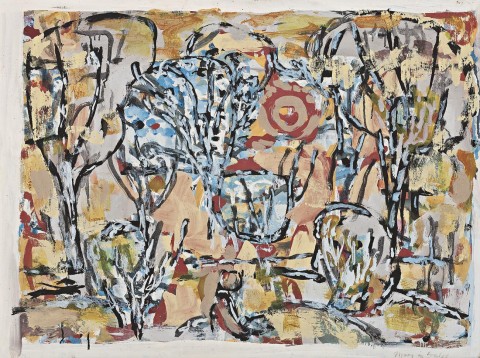

MOON IN WELLS, c.1963 – 64

IAN FAIRWEATHER

synthetic polymer paint and gouache on card on composition board

71.0 x 95.0 cm

inscribed lower right: Moon in Wells

Macquarie Galleries, Sydney (as ‘Moon in Wells’)

Robert Shaw, Sydney, acquired from the above in May 1965

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 24 November 1998, lot 47 (as ‘Moon in Wales, c.1965’)

Private collection, Darwin

Thence by descent

Private collection, Sydney

Exhibition of the Private Collection of Robert Shaw Esq., Gallery A, Sydney, arranged by the exhibitions committee of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 13 – 16 August 1966, cat. 11 (as ‘Moon in Wales, 1965’)

Collectors Exhibition, Great Synagogue, Sydney, 13 – 15 July [year unknown], cat. 13

We are grateful to Murray Bail for his assistance with this catalogue entry.

Described by Murray Bail as ‘the least parochial of Australian painters, an artist of exceptional force and originality’,1 Ian Fairweather represents without doubt one of the most highly individualistic artists ever to have worked in Australia. Born in Scotland and raised by his aunts until the age of 10, Fairweather undertook formal training at the Slade School of Art in London under Henry Tonks, while spending his evenings learning Japanese and Chinese – a pursuit which prompted him to question at an early age the primacy of the Western visual tradition. A reclusive, eternally restless spirit, throughout the 1930s and 40s he led a largely peripatetic existence, traveling extensively from London to Canada, China, Bali, Australia, the Philippines, India and beyond – ‘…always the outsider, the nostalgic nomad with a dreamlike memory of distant places and experience’.2

After his notorious attempt to sail from Darwin to Timor on a raft made of old aircraft fuel tanks, in mid-1953 Fairweather finally settled on Bribie Island, off the coast of Queensland, where for the rest of his life he lived and worked in a pair of primitive thatched huts salvaged from driftwood and scrap material. Perhaps ironically, it was during these last two decades spent in rudimentary surrounds and relative solitude that Fairweather would produce some of the finest paintings of his career, drawing with a newfound tranquility upon recollected emotions and experiences to explore beyond the merely tangible, that one enduring motif of his art – humanity. Significantly, during this period Fairweather also began to achieve international recognition, with paintings included in the landmark exhibition Recent Australian Painting at the Whitechapel Gallery, London (1961); the Sao Paulo Biennial (1963); and the European tour of Australian Painting Today (1964 – 65); and in 1965, a major travelling retrospective of his work was organised by the Queensland Art Gallery.

Dating from c.1963 – 64, Moon in Wells exemplifies well Fairweather’s confidence as a mature painter, oscillating between the figurative and an increasingly calligraphic abstraction; as he mused at the time, ‘between representation and the other thing - whatever it is. It is difficult to keep one’s balance.’3 As with many of his greatest works from this decade such as Monastery, 1961 and House by the Sea, 1967 which reference Fairweather’s seminal experiences in China thirty years earlier, or Turtle and Temple Gong, 1965 inspired by his Balinese travels, it is probable that the present work similarly derives from ‘some relic of subjective reality’,4 a mental image or memory from the artist’s itinerant life. Having recently translated and illustrated the Chinese folktale, The Drunken Buddha (published by the University of Queensland Press in 1965) Fairweather would also have been freshly attuned to the indelible influence of Chinese art – discerned here stylistically in the use of highly gestural brushstrokes and ideograms, and more philosophically, in his approach to the landscape subject which reflects the Chinese perception of nature as imbued with humanity (the shadowy trees, for example, looming large over the blue pools like ghostly figures in the moonlight). At the same time, the work may equally betray ‘an aura of his adopted landscape’ not only in its possible reference to Indigenous art, but with its strong yet meditative parched earth palette and overall ‘raucousness’ which suggests an untidiness not dissimilar to the wild, dry-tangled landscape of northern Australia.5

Indeed, as Murray Bail astutely reiterates, Fairweather’s paintings are ‘essentially ‘written’ by his own experiences’6 – each offering a rich palimpsest of heavily textured surfaces and allusions, their myriad layers eventually yielding to the inner depth or spirituality so fundamental to his highly idiosyncratic vision. For although Fairweather did not adhere to religion in a strict, ordered sense, he nevertheless appreciated the spiritual connection it could afford, comparing the experience of the faithful to that of his own artistic creativity; ‘Painting is a personal thing. It gives me the same kind of satisfaction that religion, I imagine, gives to some people’.7 The culmination of a lifelong quest to attain or comprehend some deeper existential meaning, thus the contemplative abstractions of Fairweather’s maturity powerfully transcend time or circumstance to elucidate emotions universal to all human experience. As Laurie Thomas, appreciating the originality of Fairweather’s legacy, reflected at the time: ‘He paints what he sees. But what he sees nobody else had seen until now’.8

1. Bail, M., Ian Fairweather, Bay Books, Sydney, 1981, p. 220

2. Bail, M., ‘The Nostalgic Nomad’, Hemisphere, Canberra, vol. 27, no. 1, 1982, p. 54

3. Fairweather quoted in first interview with Hazel Berg, 30 March 1963, Hazel de Berg Papers, National Library of Australia.

4. Fairweather quoted in letter to Treania Smith, 11 November 1959, Macquarie Galleries archive.

5. Bail, M., 1981, op. cit. p. 220

6. ibid.

7. Fairweather quoted in Hetherington, J., Australian Painters: Forty Profiles, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1963, p. 51

8. Thomas, L., ‘Ian Fairweather’, Art and Australia, Sydney, vol. 1, no. 1, May 1963, p. 35

VERONICA ANGELATOS