FOREST POND, 1974

FRED WILLIAMS

oil on canvas

106.5 x 91.5 cm

signed lower right: Fred Williams.

artist's label attached verso with number, artist's name, title, medium and dimensions

Rudy Komon Gallery, Sydney

The National Australia Bank Art Collection, acquired from the above in 1975 (label attached verso)

Fred Williams – recent paintings, Rudy Komon Gallery, Sydney, 5 – 30 April 1975, cat. 12 (label attached verso)

Fred Williams Recent Painting, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, 13 – 30 May 1975, cat. 12

The Seventies: Australian Paintings and Tapestries from the Collection of National Australia Bank, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 15 October – 28 November 1982

Faerber, R., ‘Impressive Magnitude’, The Australian Jewish Times, Sydney, 16 April 1975, p.42

Borlase, N., ‘A painter at his peak pushes further on’, The Bulletin, Sydney, vol. 97, no. 4954, 26 April 1975, p. 51

Lindsay, R., The Seventies: Australian Paintings and Tapestries from the Collection of National Australia Bank, The National Bank of Australasia, Melbourne, 1982, pl. 101, p. 114 (illus.)

McCaughey, P., Fred Williams, Bay Books, Sydney, reprinted 1984, pp. 262 – 265, 267

Thomas, D., ‘Official rebels’, The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 17 April 1975

Forest Pond, 1974, oil on canvas, 183.6 x 152.6 cm, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Forest Pond, 1974, oil on canvas, 182 x 152 cm, in the collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Forest Pond Triptych, 1974, oil on canvas, three panels, 107 x 91.5 cm (each) in the collection of the Sydney Opera House Trust, Sydney, illus. in McCaughey, P., Fred Williams, Bay Books, Sydney, reprinted 1984, pp. 266 – 267

210723 Fred Williams Forest pond, 1974.jpg

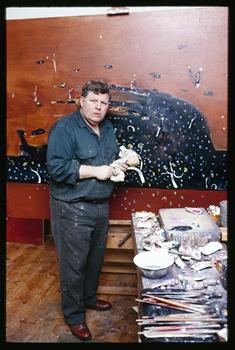

By the end of the 1960s in Australia, Fred Williams was widely acknowledged as one of the leading artists of his generation. Awarded numerous prestigious art prizes – including the 1964 Transfield Prize, the 1966 Georges Invitation Art Prize and in 1967, the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ Wynne Prize for landscape painting (which he won again a decade later) – a catalogue raisonné of his etchings had been published, and in 1970, the first major exhibition to feature his work in a public gallery took place. Titled Heroic Landscape, the exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria paired Williams with Arthur Streeton, one of Australia’s most revered and celebrated landscape painters.

Williams was never one to rest on his laurels however, and the ensuing years saw him radically change his approach, so much so, that Patrick McCaughey describes 1971 – 74 as ‘the most turbulent period in his art.’1 The most obvious shift was his palette, which was seemingly transformed with the introduction of unmixed primary colours and an array of other vivid hues. Writing in his diary in early 1972, Williams noted, ‘I have a fierce desire to paint colour… I decide to completely? alter my palette – the primary colours & the corresponding colour[s] on either side of [them on the colour wheel] plus the secondary Orange, Green & Violet – I am ready to do this.’2 The following day, in addition to listing the colours that would make up his new palette – Cobalt and Cerulean Blue, Naples Yellow, Cadmium Orange, Deep Vermilion, Winsor Violet and Titanium White, among others – he affirmed, ‘I have made a major change… & I cannot wait to try it out!’3

Alongside this new chromatic direction was a marked shift in Williams’ outdoor painting practice. While gouache, a quick-drying medium composed of watercolour mixed with white pigment, had long been his preferred medium for working outdoors, Williams now began to use oil paint on his excursions into the landscape. Painted on canvases measuring approximately 90 x 105 cm – a size which could easily be carried – his oil ‘sketches’, made directly in front of the subject, are typically more representational than works produced in the studio where, with time and distance, the details of what he had seen outdoors were often distilled and abstracted. They are also wonderfully expressive in terms of the handling of paint, reflecting Williams’ emotional response to the scene in front of him and pleasure in the subject.4 This activity fed Williams’ creativity. As he wrote, ‘I always enjoy getting out & observing things. It’s interesting to me that when I finish painting… my reflexes are so strong that I could paint anything at all – and I mean it – observation is the catalyst for me!’5

Williams painted in a diverse range of locations during these years, often in the company of artist, Fraser Fair, who described his companion working ‘swiftly, with energy and flow’, and noting that ‘the meeting with the landscape was his purpose for being alive’.6 Fair also recalled that looking for places within an hour of Williams’ home in Hawthorn, they would refer to the Age book, 50 Day Walks Near Melbourne, ideally finding a good subject within two hundred metres of the carpark.7 In early 1969, Williams had written in his diary that he intended to paint the Yarra River – known by the Wurundjeri people as Birrarung – from its source in the Yarra Ranges to its mouth at Hobsons Bay in Melbourne’s west. This ambition is reflected in many works made during the following years, culminating in the Waterfall series of 1979, and his interest in painting water, whether rivers, swamps, ponds, gorges, tidal flats or the ocean, is a strong and continuing theme throughout Williams’ oeuvre.8

210723 Fred Williams, 1981.jpg

Forest Pond was first exhibited in Williams’ solo exhibition at the Rudy Komon Gallery, Sydney, in 1975 and Georges Mora, the esteemed Melbourne art dealer, purchased it from the exhibition for the collection of the National Australia Bank (NAB). Two other Forest Pond works were also exhibited: similarly scaled, one sold to a private collection in New York, and the larger studio painting – very closely related to the NAB work in terms of its composition – was subsequently acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria.11 The significance of the subject for Williams is reflected in the fact that he also later produced a triptych which, at almost three metres long, communicates the full breadth and beauty of the scene. The triptych is part of the Sydney Opera House Trust Collection and another version of the subject, which employs a different compositional division and brighter palette, is in the Art Gallery of South Australia.12

The enthusiastic confidence Williams had in the new direction of his art proved to be well-founded. The Sydney exhibition was a commercial success and the critical response was equally positive. Alluding to the blockbuster exhibition, Modern Masters (from the Museum of Modern Art, New York), that was concurrently showing at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Nancy Borlase enthused, ‘it is here, in the Manet to Matisse mainstream, that Fred Williams belongs.’13 Daniel Thomas elaborated, ‘Fred Williams’ new paintings… have back-tracked from extreme reduction. The complexity of detail and dazzling light of the Australian landscape are triumphantly captured in… a series of grand vegetation-and-water Forest Ponds [which] pay a kind of homage to Monet… Williams knows who to compete with and who to borrow from, and it is his greedy art history that makes him our best observer of landscape. In this show he looks like the major artist we already knew him to be.’14

1. McCaughey, P., Fred Williams 1927 – 1982, Murdoch Books, Sydney, 1996, p. 225

2. Fred Williams Diary, 4 April 1972 quoted in Mollison, J., A Singular Vision: The Art of Fred Williams, Australian National Gallery & Oxford University Press, Canberra, 1989, p. 158

3. Fred Williams Diary, 5 April 1972, ibid.

4. See McCaughey, op. cit., p. 226

5. Fred Williams Diary, 6 March 1974 quoted in Mollison, op. cit., p. 184

6. Mollison, op. cit., pp. 174

7. Ibid., pp. 173-74

8. See Lindsay, R., and Zdanowicz, I., Fred Williams: Works in the National Gallery of Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1980, p. 35 and Lindsay, R., Fred Williams: Water, McClelland Gallery + Sculpture Park, Langwarrin, 2005, n.p.

9. Conversation with Lyn Williams, 16 December 2021

10. I am grateful to Lyn Williams AM for providing information about this painting and its history.

11. Forest Pond, 1974, oil on canvas, 183.6 x 152.6 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Presented by the National Gallery Women’s Association, 1975 (A14-1975)

12. Forest Pond, 1975, oil on canvas, 182 x 151 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, South Australian Government Grant 1975 (757P7)

13. Borlase, N., ‘A painter at his peak brushes further on’, The Bulletin, 26 April 1975 quoted in Hart, D., Fred Williams: Infinite Horizons, National Gallery of Victoria, Canberra, 2011, p. 139

14. Thomas, D., ‘Official rebels’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 April 1975, ibid. p. 142

KIRSTY GRANT