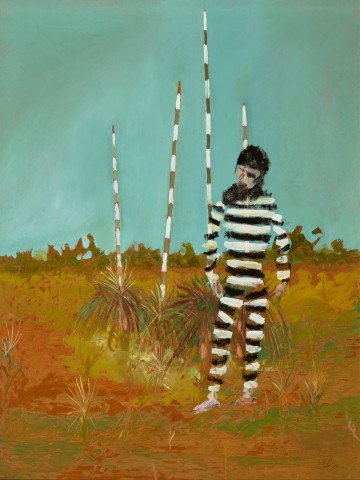

ESCAPED CONVICT, 1948

SIDNEY NOLAN

enamel on composition board

122.0 x 91.5 cm

signed and dated lower right: 1-6-48 / Nolan

Simon Sainsbury, London, by 1961

Terry Clune Galleries, Sydney

Victor Macallister, New South Wales, acquired from the above in 1964

Thence by descent

Private collection, Victoria

Gould Galleries, Melbourne

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in May 2010

Sidney Nolan: Queensland Outback Paintings, David Jones Art Gallery, Sydney, 8 - 22 March 1949, cat. 7

Sidney Nolan, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, June - July 1957, cat. 18 (illus. in exhibition catalogue pl. VI)

Sidney Nolan: retrospective exhibition, Paintings from 1937 to 1967, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 13 September – 29 October 1967; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 22 November – 17 December 1967; Western Australian Art Gallery, Perth, 9 January – 4 February 1968, cat. 38 (label attached verso, as 'Convict')

Sidney Nolan: 102 works from the first fifteen years (1939 - 53), Joseph Brown Gallery, Melbourne, 25 July - 7 August 1979, cat. 58 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

Collectable + Exceptional, The Director's Choice 2010, Gould Galleries, Melbourne, 6 May - 5 June 2010, cat. 2 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

MacInnes, C., and Robertson, B., Sidney Nolan, Thames and Hudson, London, 1961, reprinted 1967, pl. 31 (illus.)

Artists of Australia, Adelaide, 1965

Osbourne, C., Masterpieces of Nolan, Thames and Hudson, London, 1975, cat. 3 (illus.)

Clark, J., Sidney Nolan: Landscapes and Legends, International Cultural Corporation of Australia, Sydney, 1987, p. 99

230613 Nolan Escaped Convict_ cmyk.jpg

/ Copyright Agency

In 1947, Sidney Nolan made his escape from the cloying, claustrophobic world of Heide, and from the toxic symbiosis of his relationship with John and Sunday Reed.

The Templestowe cultural Camelot was falling apart. Max Harris had resigned from Reed and Harris and returned to Adelaide in September 1946. Albert Tucker went to Japan as an Allied Forces war artist in February 1947, and following the collapse of his marriage to Joy Hester, would leave again – for Europe – in September. Danila Vassilieff became a little detached following his marriage to Elizabeth Hamill in March. Hester eloped to Sydney with Gray Smith in April.

And in July, perhaps (ironically) inspired by the Reed’s enthusiastic accounts of their Sunshine State holiday in late 1946, Nolan flew off to Brisbane, famously leaving behind with Sunday the first series of his celebrated Ned Kelly paintings. There he was welcomed by the young Queensland poet Barrett Reid, a visitor to Heide during the previous summer, with whom he travelled even further north: to Bundaberg, Tamborine, Maryborough, and Fraser Island. Reid also introduced the painter to the city’s literary and artistic pocket avant-garde, and to the resources of the John Oxley Library, the local heritage collection of the State Library.

As he had with the Kelly story, Nolan discovered and delighted in the artistic potential of archival research. Initially interested in Lieutenant James Cook’s travels up the east coast of Australia in 1770, he eventually latched onto accounts of the wreck of the brig Stirling Castle on the Swain Reefs, north of K’gari/Fraser Island, in 1836. This pathetic and controversial colonial tale has been retold many times, but in 1947 the two key historical publications available to Nolan were John Curtis’s sensational version of 1838, ostensibly from Eliza Fraser’s own account, and a later and more empirically oriented history by Robert Gibbings, John Graham: convict (1937).1

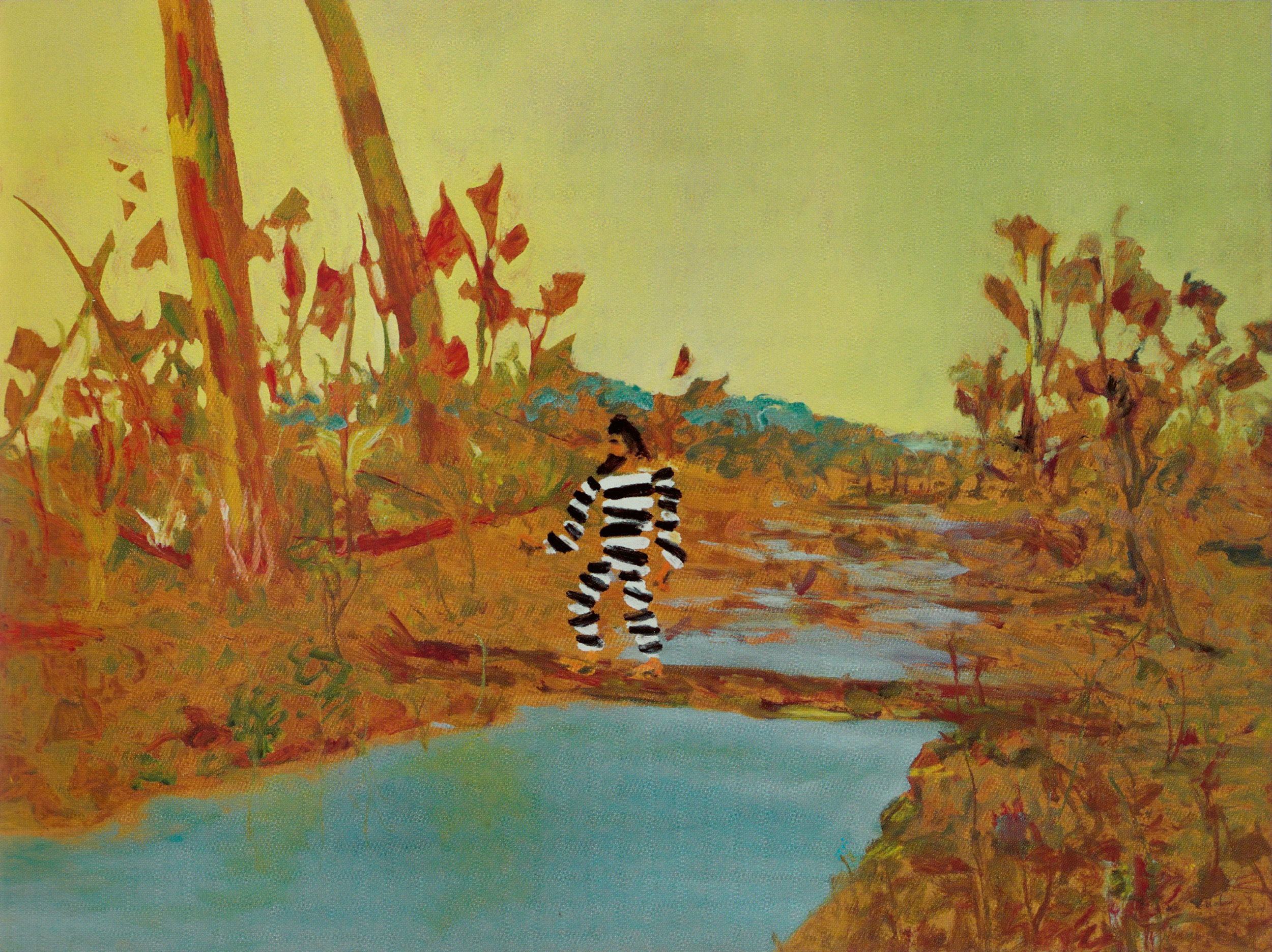

220613 DEATH OF CAPTAIN FRASER cmyk.jpg

/ Copyright Agency

The Eliza Fraser story absorbed by Nolan can be briefly summarised as follows: the Stirling Castle, en route to Singapore under the command of James Fraser, was wrecked in a storm off the coast from present-day Rockhampton, with the survivors travelling south in the ship’s boats and landing on what was then called Great Sandy Island. There a number perished, some (including Captain Fraser) at the hands of local Butchulla people, but with the captain’s wife surviving. After two months of ‘captivity’, she was eventually ‘rescued’ from the natives and guided to ‘civilisation’ at Moreton Bay by an escaped convict, David Bracefell, on whose behalf she promised to speak to the authorities. However, once within sight of settlement she reneged on her promise, and Bracefell returned to the bush.The following year, while now married to Cynthia Reed and comfortably settled in Sydney, Nolan evidently still felt keenly that he had suffered a comparable betrayal at the hands of Sunday Reed, and he completed a new series of paintings that had begun with Mrs Fraser, 1947 (Queensland Art Gallery I Gallery of Modern Art) and the Death of Captain Fraser, 1948 (Canberra Museum and Art Gallery), and included others such as the present work depicting the abandoned Bracefell alone in the bush.

However, as so often since his army days in the Wimmera, Nolan’s narrative figuration is preceded by and fundamentally embedded in the dumb, haptic experience of landscape. From further travels, in northern Queensland, Nolan began in May with a sequence of pictures of the Gulf Country around Normanton, including (inter alia) Windy Plain, 1948 (University of Western Australia); Carron Plains, 1948 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), and Blackboys, 1948 (private collection). The North Queensland dry sclerophyll landscape that occupies the bottom half of the present picture is as raw as it is rich; a desert plane of iron oxide red, ochre yellow, olive green and raw Masonite. Above the conventional-compositional-rule-breaking central horizon line is a flat, uninflected, cloudless, tropical dry season pale blue firmament, and where the sky meets the earth, Nolan describes the distant bush not by building up pigment over a flat ground, but by ‘cutting in’ around suggestive tonal variations. This gives the foliage a tattered, fluttering, flag-like indeterminacy, suggestive of the shimmering, uncertain perception of a mirage, or of things seen at the edges of vision.

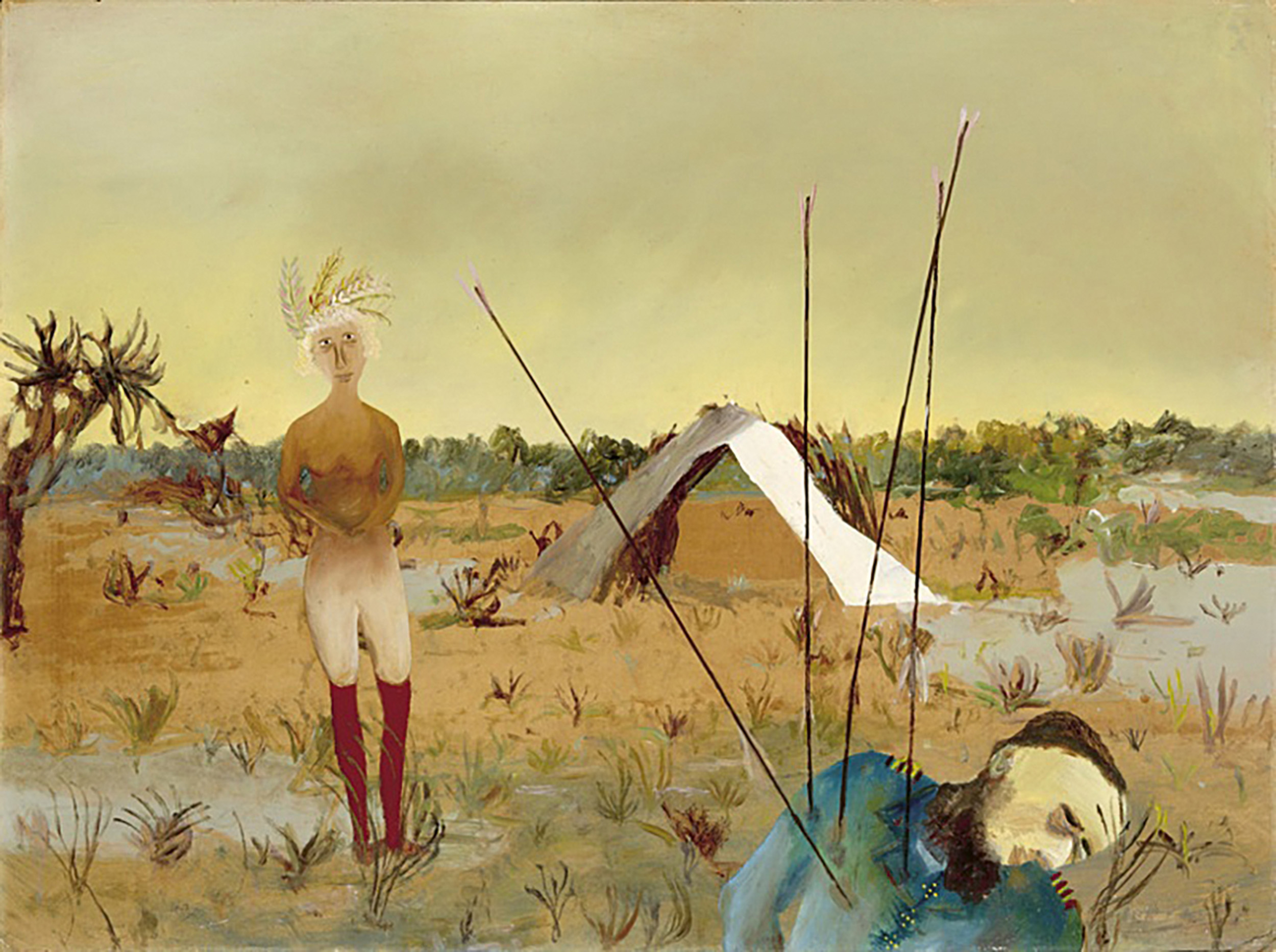

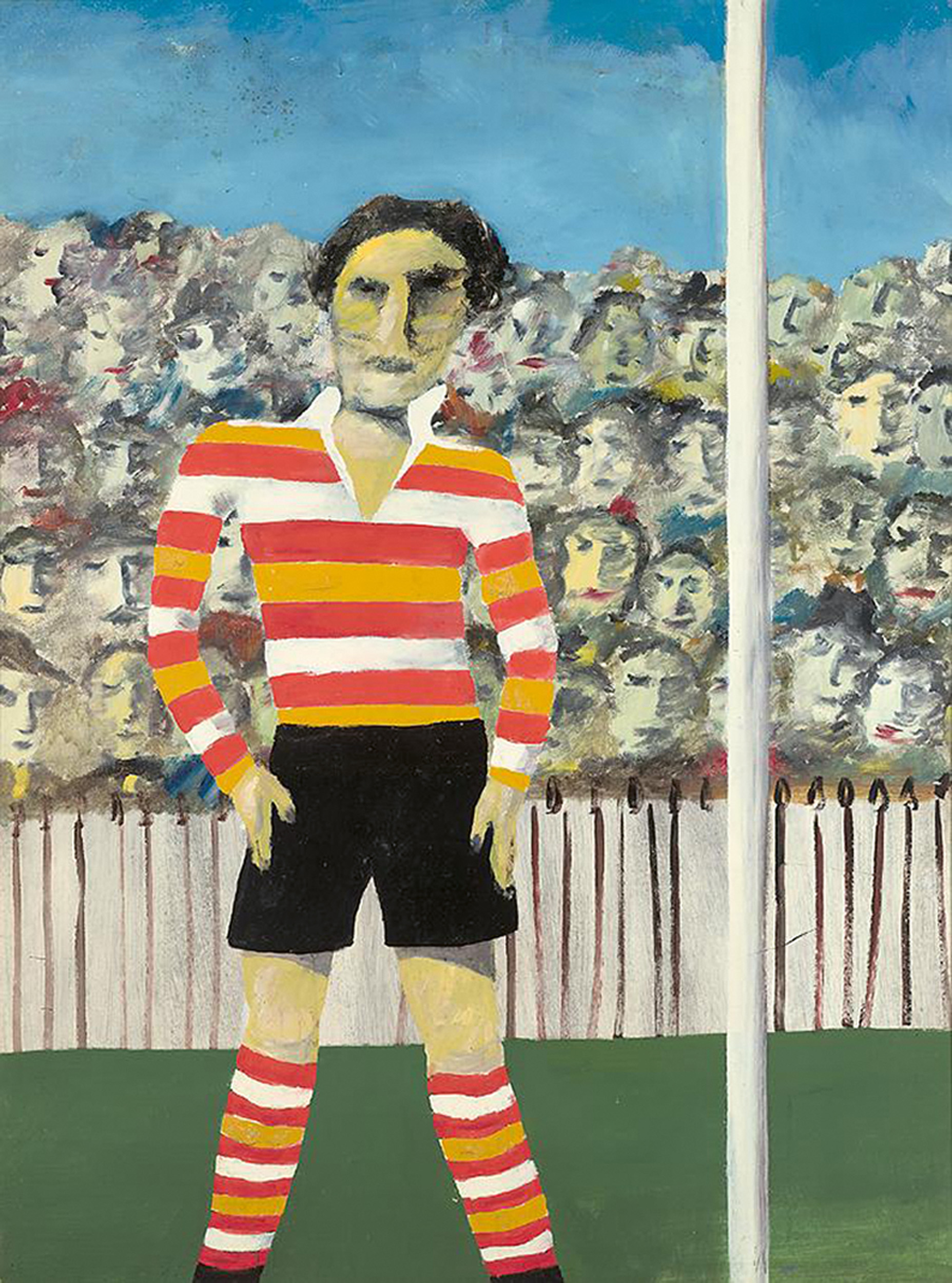

Then there is the prominent xanthorrhoea or grass tree, formerly commonly known to settler Australians as the ‘black boy’, a plant which produces black, spear-like ‘scapes’, rising from the crown of a green needle or pompom skirt at the top of its trunk. The foreground landscape in Escaped Convict is enlivened by detonations or compact cascades of these grass tree needles. The scapes which here pierce the empty sky flower in spring, or after fire, with white blossoms distributed spirally up the spike. Before the whole spike becomes sheathed in white, the emerging blooms can create a spotty, banded effect. For Nolan, this was honey; his precedent oeuvre is clotted with stripey incidents. There are heraldic bars in the early 1940 abstract monotypes, in the flags of Rimbaud Royalty, 1942 (Heide Museum of Modern Art); in the towel in Bathers, 1943 (Heide Museum of Modern Art); in the tiger stripes of the brand on the sack in Flour Lumper, 1943 (National Gallery of Victoria); in the football jumper of Footballer, 1946 (National Gallery of Victoria), and they recur in the drapery folds and columnar flutings of his designs for Sam Hughes’s Sydney University Dramatic Society production of Jean Cocteau’s Orphée and Shakespeare’s Pericles later in the year.2

220613 Sidney Nolan Floor lumper_cmyk.jpg

/ DACS / Copyright Agency

And that is where the picture rested, until the addition of the inevitable mythic figure, Nolan’s ‘recurrent trope – the outsider set against an environment which resists occupation.’3 Building on the invented portraiture of his ‘colonial heads,’ a series painted towards the end of the Ned Kelly campaign of 1946-47, Nolan here drops an anonymous 19th century bearded head on top of a roughly-sketched zebra-striped convict figure. What Colin MacInnes calls the ‘skeletonic bars’4 of the prison uniform do not give us a body fully-modelled in space, but rather an abstract, a cypher, an almost-invisible man; as MacInnes puts it, ‘the figure is … insubstantial, almost like a vibration in the air, however palpable.’5 The background landscape can be perceived between the black and white bars, while the scape of the right-hand grass tree gives Bracefell both a spine and a hangman’s rope. Close examination even suggests some sort of continuity between the bands of Captain Fraser’s epaulettes in Death of Captain Fraser, and the striations of the convict uniform, and between the xanthorrhoea scapes and the Aboriginal spears that pierce Fraser’s body.

In Nolan’s desk diary for 24 March 1952 there is a rare, candid self-exploration, ‘one of [his] longest philosophical self-discussions.’6 Responding to Eric Bentley’s book The Cult of the Superman, and considering Ned Kelly, Burke and Wills and David Bracefell, the artist admits that ‘the question is still open but apparently I am trying to formulate some conception of a colonial hero.’7 This key question would remain open for the rest of Nolan’s career.

Another, more subliminal aspect of this work also bears mention: its relationship to First Nations culture.

220613 NOLAN FOOTBALLERS_cmyk.jpg

/ DACS / Copyright Agency

As Jane Clark observed in discussing Blackboys, ‘the trunks of the … grass trees are marked … like dreamtime Aboriginal warriors painted for a corroboree,’8 and it is interesting to note that the year after this work was painted, Nolan was quoted in the Telegraph as saying: ‘I am of the opinion that the Australian aboriginal is probably the best artist in the world. Recently we toured Central Australia, and the aboriginal art amazed me. The aborigine has a wonderful, dreaming philosophy which all Australian artists should have.’9 Carron Plains was illustrated 30 years later in Elwyn Lynn’s Sidney Nolan’s Australia, and his quotation from the artist about this work runs: ‘I wanted to grasp the idea of dry winds blowing through the trees, with the blackboys being trees or perhaps native boys; it’s a lyrical fantasy.’10 Moreover, while it may be anachronistic, it is nevertheless stimulating to consider the stripes of the xanthorrhoea and of Bracefell’s convict uniform as somehow coincident with those of Central Desert painting of the 1990s and 2000s: Turkey Tolson Tjupurulla’s eye-candy Straightening Spears works, or the awelye body paint designs of Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Minnie Pwerle.

Nolan’s Mrs Fraser series would be reiterated in sequences from 1957 and 1962, but its powerful ‘fusion of symbolism and reality’11 was first exhibited at David Jones’ Art Gallery, Sydney in March 1949.12 The exhibition Queensland Outback Paintings included both Mrs Fraser pictures and individual rural historical fantasies such as Dog and Duck Hotel (1948, private collection), Huggard’s Store, 1948, (University of Western Australia), and Little Dog Mine, 1948, (Holmes à Court collection, Perth). In many ways this was the show that marked the beginning of Nolan’s national success, recognition which would be cemented in the following year’s Exhibition of Central Australian Landscapes.13 Hal Missingham purchased two pictures for the Art Gallery of New South Wales, while the Sun’s reviewer, Harry Tatlock Miller, declared that the work ‘makes an amazing impact and leaves an indelible impression … I can remember no exhibition by a contemporary Australian artist which with such seemingly disarming innocence of eye and hand, reveals so much individuality of vision. He gives us the sensation of seeing and knowing our own country, both its landscape and its legend, for the first time.’14

1. Curtis, J., Shipwreck of the Stirling Castle, containing a faithful narration of the dreadful sufferings of the crew, and the cruel murder of Captain Fraser by the savages… George Vertue, London, 1838; Gibbings, R.,, John Graham: convict, J. M. Dent & Sons, London, 1937. There was also an extensive retelling in Russell, H., Genesis of Queensland, Sydney, 1888. Later in the 20th century, Nolan’s friend the novelist Patrick White would publish a fictionalised account – White, P., A fringe of leaves, Jonathan Cape, London, 1976 – its original dust jacket reproducing Nolan’s Mrs Fraser and convict, 1962 – 64. The tale continues to fascinate; a postcolonial, trans-media reading can be found in Schaffer, K., In the wake of first contact: the Eliza Fraser stories, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995, while more recently, Larissa Behrendt provides a developed First Nations perspective in Behrendt, L., Finding Eliza: power and colonial storytelling, Queensland University Press, St Lucia, 2016.

2. There may be another source for the striped spear: the St Andrew’s cross spider. As is already known (from his celebrated borrowing of an aerial view of Longreach for the Ned Kelly series’ The watch tower, 1947 (National Gallery of Australia), Nolan was a consumer of the Australian Geographical Society’s popular post-war pictorial magazine Walkabout. A close-up image of this eastern Australian arachnid, its web decorated with a zig-zag ‘X’ known as the ‘stablimentum’, appeared in the 1 April 1948 edition of Walkabout, p. 27 (photograph: Norman Laird): see https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-739044803/view?partId=nla.obj-739070666#page/... (accessed June 2023). In this image, the creature’s striped tapered legs resonate strongly with Nolan’s grass tree scapes.

3. Seear, L., ‘A wave to memory: Sydney Nolan Mrs Fraser’, in Ewington, J., and Seear, L., (eds.), Brought to light: Australian art, 1850 – 1965: from the Queensland Art Gallery collection, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1998, p. 202

4. MacInnes, C., Sidney Nolan, Thames and Hudson, London, 1961, p. 22

5. ibid., p. 88

6. Nolan cited in Underhill, N. (ed.), Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his own words, Viking, Melbourne, 2007, p. 22

7. Nolan, cited ibid. See also Bentley, E., The Cult of the Superman: a study of the idea of heroism in Carlyle and Nietzsche, with notes on other hero-worshippers of modern times, Robert Hale Ltd., London, 1947.

8. Clark, J., Sidney Nolan: Landscapes and Legends, International Cultural Corporation of Australia, Sydney, 1987, p. 99

9. ‘Aborigines “best artists”’, Daily Telegraph, 17 December 1949, p. 5

10. Lynn, E. (ed.), Sidney Nolan’s Australia, Bay Books, Sydney, 1979, p. 82

11. Haefliger, P., ‘Masterpieces of modern Australian art’, Sydney Morning Herald, 2 November 1949, p. 2

12. An earlier exhibition of twelve Fraser Island pictures was shown at the Moreton Galleries, Brisbane, in February 1948, but this show largely comprised landscapes. It was not well received by local critics, who described the work as ‘meanderings in pictorial experiment’ and ‘blatant extremism’ (‘“Shock tactics” shock’, Courier-Mail, 18 February 1948, p. 2)

13. Central Australian Landscapes, David Jones’ Art Gallery, Sydney, March – April 1950

14. Tatlock Miller, H., ‘Amazing impact by Australian artist’, The Sun, Sydney, 8 March 1949, p. 8

DR DAVID HANSEN