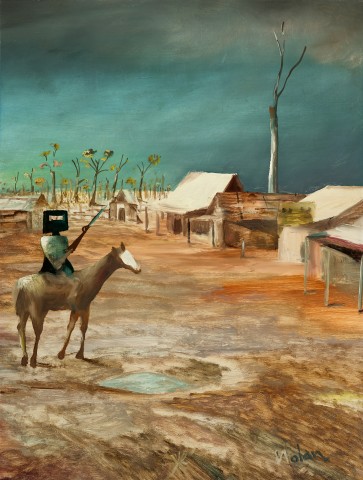

EARLY MORNING TOWNSHIP, 1955

SIDNEY NOLAN

Ripolin enamel and oil on composition board

85.5 x 64.0 cm

signed lower right: ᴎolan

signed, dated and inscribed verso: ADELAIDE / M. BONYTHON / KELLY SERIES / EARLY MORNING TOWNSHIP / 16/2/55 / nOLAN

Redfern Gallery, London

Private collection

Sotheby's, Melbourne, 17 April 1989, lot 514

Private collection

Gould Galleries, Melbourne

Sotheby's, Melbourne, 22 April 1996, lot 21

Henry Krongold, Melbourne

The Estate of Paul Krongold, Melbourne

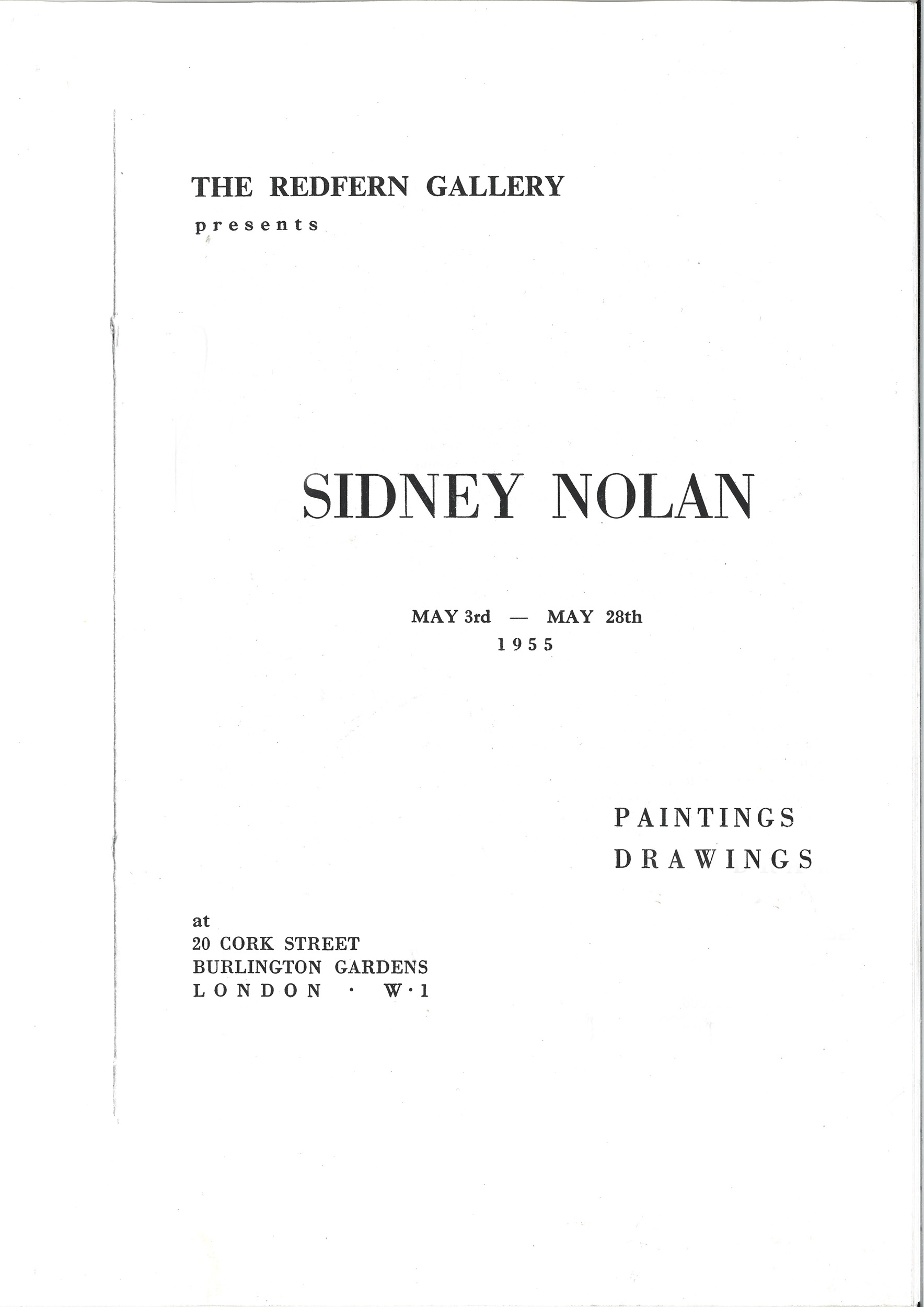

Sidney Nolan: Paintings, Drawings, Redfern Gallery, London, 3 – 28 May 1955, cat. 11

Treasures Revealed: Modern Australian Art, Gould Galleries, Melbourne, 1 – 24 September 1995, cat. 10 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

Sidney Nolan is well-known for his iconic depictions of the 19th century outlaw Ned Kelly. The most famous of these paintings are the works in the first Kelly series painted in Melbourne at Heide, the home of John and Sunday Reed, between 1946 and 1947. At the conclusion of his time there, the series was given by Nolan to the Reeds and subsequently gifted by Sunday to the National Gallery of Australia in 1977. The suite of 26 works remains possibly the best-known series of paintings in Australian art. Given the personal connections, Nolan’s separation from that seminal group of paintings was not without regret. In subsequent years, the artist would return to the Kelly saga.

Growing up in an extended Irish clan, Sidney Nolan was enthralled by the tales of his grandfather, William (Bill) Nolan, a policeman in rural north-eastern Victoria who had been involved in the pursuit of the Kelly Gang and its most famous member, Edward (Ned) Kelly. The complex story of the notorious band of bushrangers begins when Constable Fitzpatrick visits the Kelly home at Eleven Mile Creek, near the town of Greta, in April 1878. According to the Kelly family, Fitzpatrick indecently manhandled Ned’s sister Kate, leading to an altercation with Dan Kelly. Fitzpatrick’s version of events is unsurprisingly contrary, reports of which led to arrest warrants being issued for Ned and Dan. Thus begins the saga of banditry to follow. After many travails and encounters the Gang meets its end in a gun battle with police at the Glenrowan Hotel. Ned Kelly is captured and later executed by hanging at the Old Melbourne Gaol on 11 November 1880. In his brief yet highly publicised career, Ned Kelly had become something of a local hero, especially so amongst the working-class Irish of Victoria who recognised the unfairness of the police in their dealings with the less privileged members of society. Such expressions as ‘Game as Ned Kelly’ were common household sayings.

230244 CAT COVER (NOLAN)_B&W.jpg

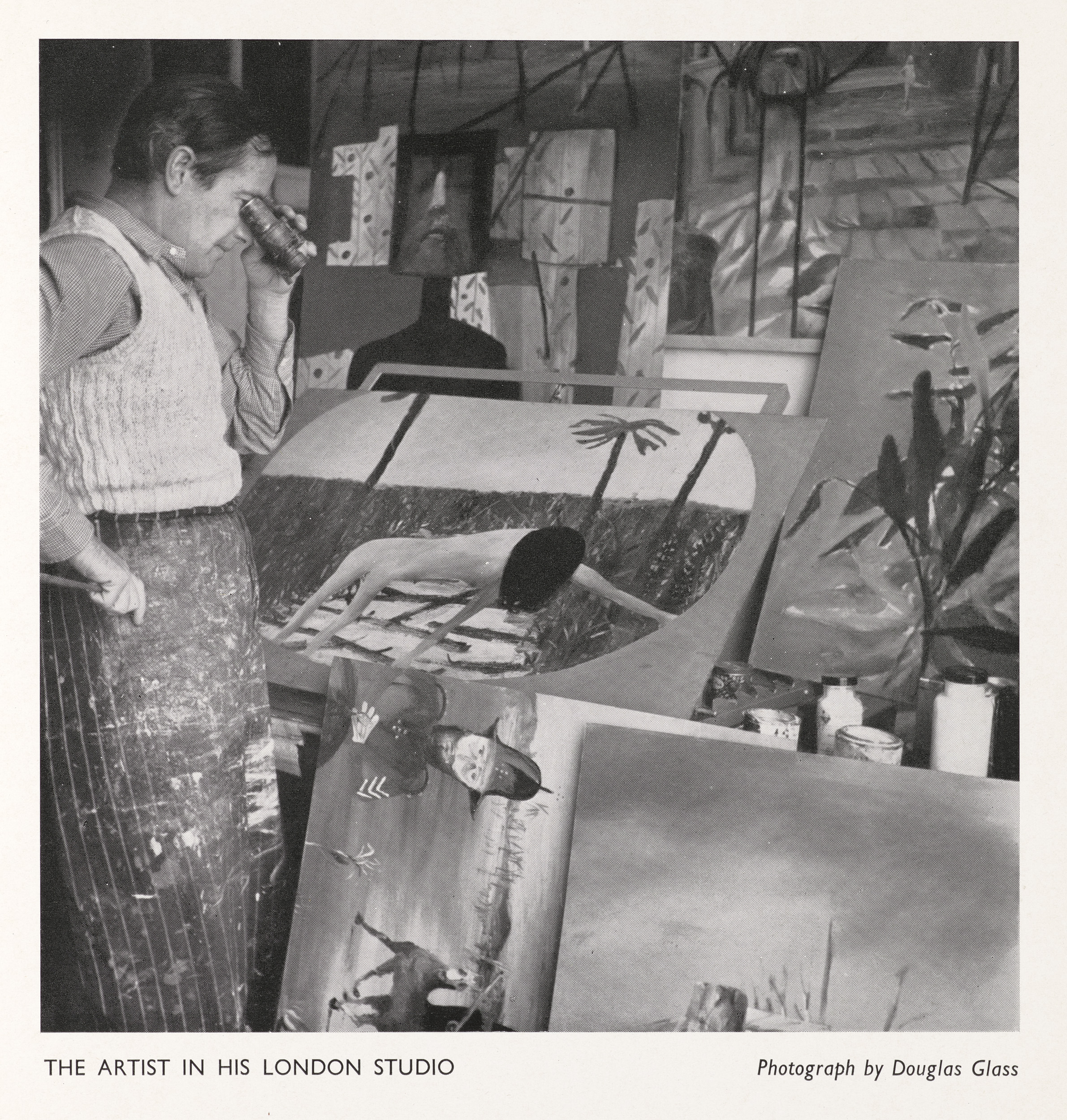

‘Sidney Nolan: Paintings, Drawings',

Redfern Gallery, London, 3 – 28 May 1955

Kelly was distinguished not only by his actions, but equally by his home-made suit of armour, replete with iron helmet. The square outline of this iconic helmet allowed Nolan to make a mental association between Kelly’s mask and the 1915 painting Black Square, created by Russian Constructivist artist Kazimir Malevich. Nolan repurposed the abstract form as a figurative motif, thus creating a symbol that became synonymous with the artist and Kelly alike. By the time that Nolan turned his attention to Kelly, the saga was viewed in elite circles as a shameful colonial episode, certainly not one that could elevate the standing of Australia in any meaningful way. For Nolan however, Kelly’s preparedness to stand against the world marked him out as one who could transform and transcend his cultural and historical moment. When he embarked on the creation of the Kelly paintings, Nolan was himself ‘on the run’, absent without leave from his army post, informing his personal relationship with the cult outlaw.

230244 NOLAN The Glenrowan siege_cmyk.jpg

DACS / Copyright Agency 2023

Nolan was completely familiar with the part of Victoria that is sometimes called ‘Kelly Country’, having spent many childhood summers there with relatives. The artist also immersed himself in the available literature on Kelly. This included contemporary newspaper reports, J. J. Kenneally’s ‘The Complete History of the Kelly Gang and their Pursuers’, and the voluminous ‘Royal Commission on the Police Force of Victoria’, 1881, which occurred in the wake of the ‘Kelly outrages’.1 According to Nolan’s biographer, Brian Adams, Nolan along with the poet, critic and publisher Max Harris, also travelled by train to the town of Glenrowan, seeking first-hand knowledge of the Kelly saga. From the outset, Nolan and Harris received a frosty reception; the locals were ill-disposed to discussing the Kelly story. This was repeated also when the pair located Ned Kelly’s younger brother Jim. The now aging rustic would not even shake hands with the probing artist. Such experiences did not deter Nolan from bringing the elements of historical research, myth and landscape to bear on his Ned Kelly paintings. When the paintings were first exhibited in Melbourne in 1948, Nolan presented them with quotes taken from historical sources, thus cementing the play of text and image in the reading of the work.

On 17 August 1950, Sidney Nolan and his wife Cynthia (née Reed) sailed for Europe, basing themselves in Cambridge and travelling to Portugal, Spain, France and Italy. Following subsequent trips to Australia, the couple again set sail on 22 October 1953 and settled permanently in London.2 The shift was to prove decisive in Nolan’s artistic life with a new maturity entering his paintings. Between 1954 and 1956 Nolan produced a group of oil and enamel on board paintings, some as a direct reworking of the first Kelly series. In the new compositions, greater focus was given to the fateful Glenrowan Siege, a confrontation that ended the Gang’s reign of terror in a spectacular fashion. Such paintings included preliminary renderings of the town of Glenrowan, solitary images of the iron-helmeted outlaw, the wounding of Ned Kelly outside of the Glenrowan Hotel, and the aftermath of the siege wherein police set fire to the hotel. In later works, Kelly was presented less as a historical person than a figure of mythic proportions, at times acquiring universal appeal.

Within this spectrum, Early Morning Township, 1955 is an augury of the skirmish to come. Ned Kelly is seen studying the township in the cool light of morning. The town sleeps while Kelly, set to one side of the composition, sits astride his steed, rifle in hand. The outlaw is still but his dappled mount sniffs the air, perhaps sensing the danger to come. The composition can be read as the prelude to the violence of the Glenrowan Siege; a poignant moment as Kelly contemplates the polite society to which he will never belong. It is also a counterpoint to an important painting purchased in 1955 by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Titled Glenrowan Siege, 1955, this work shows the ruined aftermath of the battle in which many of the Kelly Gang members were killed.

230244 cmyk.jpg

(Second Ned Kelly series), 1955

All rights reserved, DACS /

These two paintings were featured in Nolan’s first solo exhibition in London, Sidney Nolan: Paintings and Drawings, at the Redfern Gallery, running from 3 May to 28 May 1955 organised by the influential gallery director, Harry Tatlock Miller. Originally from Geelong, Miller worked as journalist and art critic, and along with his partner, the artist and set designer Loudon Sainthill, collaborated on several books related to tours of Australian theatre. In Melbourne in 1939, Nolan had been commissioned to design the sets for Serge Lifar’s production of Icare, a project that had originally been earmarked for Sainthill. Nolan’s lucky break did not deter Miller from giving Nolan a favourable review. In 1949, in the Sydney Sun, Miller writes: ‘[Nolan] gives us [Australians] the sensation of seeing and knowing our own country, both its landscape and its legend, for the first time.’3 In London the pair met via Nolan’s wife Cynthia, who knew Miller from Australia. The exhibition featured nineteen Kelly paintings including catalogue entries nos. 1-17 and nos. 37-38. Early Morning Township is listed as no. 11 in the catalogue, with Glenrowan Siege as no. 5. For Patrick McCaughey, the new Kelly paintings were ‘monumental and grave…had a tragic grandeur, and were quite different from the lively, more anecdotal, series of 1946 – 47.’4

In similar fashion, the journalist Colin McInnes wrote:

In the new Kelly series of 1954 – 55, the ‘naïve’ style has gone, and the invented shapes are intellectually more coherent and plastically more ingenious: the colours, unlike those of the earlier landscapes, are luminous, rich, and varied; while the presentation of the Kelly myth has gained a new magic and imaginative power. Nolan has given the hero his metallic face and body as he rides and strides through the enormous Bush, striking terror and constantly facing it. The mood of these pictures is sardonic, brutal, sad and tender. The story unfolds itself painfully and poetically in the successive episodes, and all the loss and sorrow of a rare young life thrown on to the scrap-heap are dignified, ennobled, and redeemed.5

McInnes’s reference to tenderness and ‘a story that unfolds poetically in successive episodes’ is vividly apparent in Early Morning Township. It is also worth considering that by the time Nolan was producing these works, not only had he painted numerous important bodies of paintings, but he had now established himself as Australia’s foremost modern artist at an international level. He had been appointed, in 1954, Australian commissioner at the Venice Biennale.

220613 dh160668_cmyk.jpg

DACS / Copyright Agency

Deutscher and Hackett, Sydney 15 March 2017

Early Morning Township distils many of Nolan’s key artistic aspirations to create narratives that were quintessentially Australian, lyrical in nature and universal. The Central Australian landscapes and Burke and Wills series of 1950, the 1953 Drought series of paintings featuring the desiccated carcases of animals, the religious paintings of 1951 - 52 depicting saints in the Australian outback – all had been completed in the leadup to the mid 50s Kellys. Notably, the iron-helmeted figure in Early Morning Township is presented centaur-like, at one with his equestrian mount, and similar to the creature of ancient Greek legends. Increasingly, Nolan would introduce mythic elements into the Kelly paintings encouraging the emergence of deeper implications of the outlaw’s travails. In a letter dated 1 April 1951, written to his close friend the artist Albert Tucker, Nolan reflected on his encounters with early European art, suggesting ‘the painters who moved me most (El Greco & Giotto) seemed men primarily of faith….The painting is wonderful in the sense that it is a painting of wonderment.’6 Comments such as this highlight Nolan’s search for a deeper pictorial language, one that transcended a mere recollection of narrative. Elements such as the blue sky and reductive umber landscape used by Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel frescoes (1304 - 1306), which Nolan visited, along with Giotto’s rendering of Christ entering Jerusalem astride a donkey, prior to his crucifixion, suggest references for Early Morning Township.

230244 PLACEHOLDER ONLY _cmyk.jpg

DACS / Copyright Agency

Institutional purchases from this period reflect the importance of the Kelly paintings from the mid 1950s. Additional to the painting purchased by MOMA New York, Kelly Spring, 1956 was acquired by The British Council. In 1959, the Contemporary Art Society gifted Death of a Poet, 1954 to the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. The Tate Gallery also acquired Glenrowan, 1956 - 57 from Nolan’s large solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London. Turning to Australian art collections, The Art Gallery of New South Wales has a smaller Ned Kelly painting completed just six days prior to Early Morning Township, and the Art Gallery of Western Australia is home to The Disguise, 1955 also from the Kelly Series. The National Gallery of Australia in Canberra has Kelly Crossing Bridge, 1955, while the National Gallery of Victoria is home to Kelly and Horse, 1955. The unquestionable importance of these works in 20th century Australian art cannot be understated. Of the remaining ten or so Ned Kelly paintings from the Redfern exhibition outside of public collections, Early Morning Township stands as a rare and significant work. In the 21st century, Nolan continues to be regarded as Australia’s most important 20th century artist, with ongoing exhibitions, biographies, feature-length documentaries, centenary celebrations and research initiatives that continue to plumb the seemingly limitless depths of Nolan’s creative outpourings. Nolan’s depictions of Ned Kelly however remain his singular crowning achievement.

1. Royal Commission on the Police Force of Victoria, 1881, National Library of Australia, Canberra, Registry Number Aus 68-1548

2. Underhill, N., Sidney Nolan: A Life, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2015, p. 62

3. Tatlock Miller, H., ‘Amazing Impact by Australian Artist’, The Sun, Sydney, 8 March 1949, p. 8

4. McCaughey, P. (ed.), Bert & Ned: The Correspondence of Albert Tucker and Sidney Nolan, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006, p. 179

5. McInnes, C., Sidney Nolan, Thames & Hudson, London, 1961, p. 31

6. Sidney Nolan to Albert Tucker, 1 April 1950, in McCaughey, P. (ed.), ibid., p. 122

DR DAMIAN SMITH

Secretary, AICA Australia (International Association of Art Critics, UNESCO sponsored)

Director, www.wordsforart.com.au