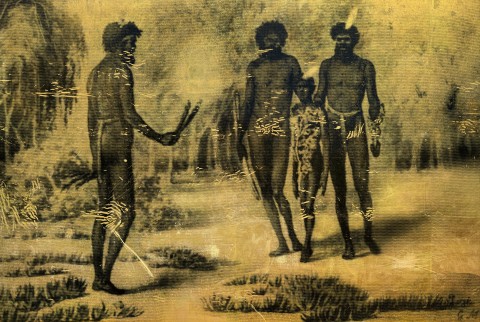

AUSTRALIA II: PEACE, 2012

BROOK ANDREW

mixed media on Belgian linen

200.0 x 300.0 cm

Collection of the artist, Melbourne

Artevent, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 16 October 2012, lot 5, donated by the above

Private collection, Melbourne

2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 1 March – 11 May 2014 (another example)

Mitzevich, N., 2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2014, pp. 12 – 13 (illus., another example), 62 (dated as 2013)

AUSTRALIA IV, 2013, mixed media on Belgian linen, 200.0 x 300.0 cm, in the collection of the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth

AUSTRALIA VI: Theatre and Remembrance of Death, 2014, mixed media on Belgian linen, 200.0 x 300.0 cm, edition 1/3 + 2AP, in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

91.2014##MM_web.jpg

While searching for anonymous ethnographic portraits of his Indigenous forebears in the imperial university museums of London in 2007, contemporary Wiradjuri and Ngunnawal artist, Brook Andrew, stumbled upon a little-known colonial document which led him to interrogate – ‘where is truth in representation when myth-making is integral to history?’1 – in two suites of monumental works: The Island and Australia. The album of prints he had found was commissioned by Prussian geologist and naturalist William Blandowski, illustrating his encounters with First Nations Australians during the 1850s, a time of significant ecological and social change. The chosen vignettes, filtered through the lens of the outsider and coloured by Romantic European notions of the ‘noble savage’, depict what the explorer had considered the most bizarre and dramatic aspects of Aboriginal life. They present a fanciful story of first contact, copied and retold several times, tinted with the same gothic fantasy of John Glover’s contemporaneous paintings of Tasmania’s Palawa enjoying full possession of their homelands during a violent chapter of Australian history.

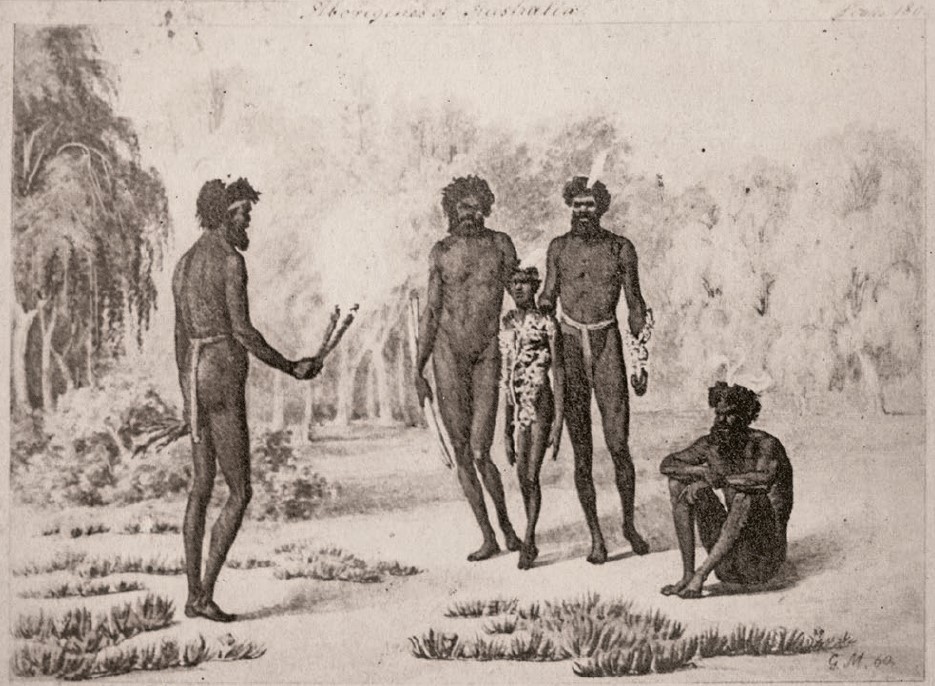

Brook Andrew’s impressive tableau, AUSTRALIA II: Peace, 2012 elevates to a grand scale Blandowski’s image of a mysterious diplomatic ceremony of Wiradjuri men on the Bogan River in North-West New South Wales.2 This work is one of six scenes (AUSTRALIA I – VI, 2012 – 2014) that re-present etchings by Gustav Mützel, a German artist who never stepped foot on the Australian continent. Commissioned by Blandowski to immortalise the findings of his expedition to the Murray Darling basin in 1856 – 57, Mützel used original ethnographic sketches executed by Blandowski himself and his colleague Gerard Kreft to create composite illustrations ten years after the original expedition. The drawings since lost, these images today remain in minuscule photographic albumen prints published in Blandowski’s illustrated account, Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen, 1862, only two full copies of which are extant in libraries in Europe.3 Largely unseen by Australian people, Indigenous or otherwise, their revelation by modern-day scholars and artists allows for a crucial post-colonial critique of narrative and image-making.

Mutzel.jpg

Appropriated and transformed by Andrew, Mützel’s minute bookplate has been enlarged to a vast scale and applied by a screen-printing process to a coloured foil support, a dazzling format. Presenting their ‘primitive’ warrior virility in stiffly theatrical stances, the composition mirrors Neoclassical history paintings in the highest ranks of the French Salon. A young boy, his chest adorned with a large leafy branch, is flanked by two men, each with a hand on his shoulder, in a tense conversation with a third man carrying smoking sticks. The drama of this cultural performance remains mysterious and opaque, its sacred nature supposedly concealed to uninitiated viewers.

The notes accompanying Blandowski’s sketch describe an offering of a boy as ‘a peace emissary’ and surprisingly reveal that this encounter was not observed directly. It derives instead from Sir Thomas Mitchell’s observation during his second exploration expedition following the Bogan River downstream to its confluence with the Darling some twenty years before, in 1835. Interestingly, the published record of Mitchell’s exploration in 1839 was accompanied by the first version of this image – a detailed engraving by G. Barnard derived from Mitchell’s own drawing. Within this print, titled ‘First Meeting with the Chief of the Bogan Tribe’ we see more clearly the emu feathers and body paint adorning the bodies of the men, the Chief on the right, and the green boughs that covered the ‘very fine’ boy’s body, although his ‘holiday look of gladness’ described in the account is not so discernable.4 In this ‘original image’ and in Blandowski’s version, there are several additional figures: the explorer Mitchell and his horse, and a seated Indigenous man and dog, all of whom Andrew has removed from his monumental composition.

Plucking the ‘noble savage’ out from colonial archives, Andrew’s AUSTRALIA II places them instead in images of a heroic scale hitherto denied to ‘ethnographic’ subjects. Harnessed by a highly reflective gold foil, the light of discovery shines unevenly across the surface of the artwork. The glittering surface, scratched away by Andrew in several areas, alludes to the idealism of peace ceremonies in an untouched arcadia. An expression of Enlightenment humanism, these images nevertheless placed the European explorer at the apex and centre, observing and analysing for posterity those cultures on the periphery. By removing these European interlocutors from the composition, Andrew questions the very nature of representation and the interaction of divergent colonial agendas.

Following their successful first presentation at Dark Heart: The 2014 Adelaide Biennial, one example from this series, the disquieting AUSTRALIA VI: Theatre of Death and Remembrance, was acquired by the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Since November 2021, it has been included in the current re-hang of the gallery’s Grand Courts, placed amongst idealised Impressionist landscapes by white settlers such as Arthur Streeton and Sydney Long which – devoid of their Indigenous inhabitants – have defined national imagery for the better part of the last hundred years.

1. Andrew, B., ‘Remember How We See: The Island’, in Allen, H., Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2010, p. 165

2. Allen, ibid., p. 96

3. Allen, H., ‘Authorship and Ownership in Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen’, Australasian Historical Archaeology, Sydney, vol. 24, 2006, p. 32

4. Mitchell, T. L., ‘Three Expeditions Into the Interior of Eastern Australia with Descriptions of the Recently Explored Region of Australia Felix, and of the Present Colony of New South Wales, vol. 1’ in Journal of an Expedition Sent to Explore the Course of the River Darling, in 1835, by Order of the British Government, 2nd rev., T. & W. Boone, London, 1839, p. 194

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH