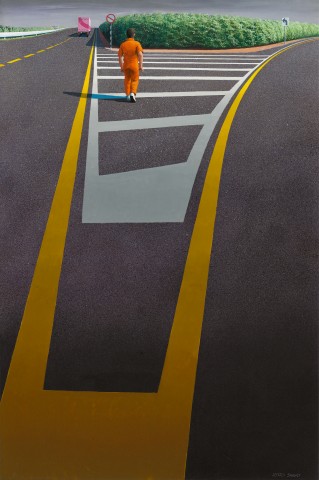

THE AREZZO TURN-OFF II, 1973

JEFFREY SMART

oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas

119.0 x 79.0 cm

signed lower right: JEFFREY SMART

Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney

Private collection, Sydney, acquired from the above in 1973

Australian Galleries, Melbourne (label attached verso)

Private collection

Christie’s, Melbourne, 27 November 2001, lot 69

Private collection, Melbourne

Jeffrey Smart, Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney, 30 November – 31 December 1973, cat. 10

Jeffrey Smart: A Review., The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 17 June – 8 August 1982, cat. 38

Urban and Urbane: paintings, drawings & prints, Rex Irwin Art Dealer, Sydney, 28 June – 23 July 1994, cat. 23 (label attached verso)

Jeffrey Smart Retrospective, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 27 August 1999 – 6 August 2000, cat. 44, and touring to the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane; Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne

Australian Galleries, Melbourne, September 2000 (label attached verso)

Quartermaine, P., Jeffrey Smart, Gryphon Books, Melbourne, 1983, cat. 618, pp. 76, 113

McDonald, J., Jeffrey Smart / Paintings of the '70s and '80s, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1990, cat. 79, p. 157

McCulloch, A & S., The Encyclopedia of Australian Art, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p. 651 (illus.)

Capon, E., Jeffrey Smart Retrospective, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1999, cat. 44, pp. 21, 135 (illus.), 208

The Arezzo Turn–off I, 1973, synthetic polymer paint and oil on canvas, 80.0 x 100.0 cm, private collection

Sketch for The Arezzo Turn–Off II, 1973, gouache on paper, 21.0 x 18.0 cm, private collection

We are grateful to Stephen Rogers, Archivist for the Estate of Jeffrey Smart, for his assistance with this catalogue entry.

J SMART.jpg

‘Many of my paintings have in their origin a passing glance. Something catches my eye, and I cautiously rejoice because it might be the beginning of a painting. Sometimes it’s impossible to stop and sketch because I saw it from a train or a fast-moving car on the autostrada. And it can happen that when I go back to that place, I wonder what on earth it could have been that enchanted me – it isn’t there. Enchantment is the word for it…’1

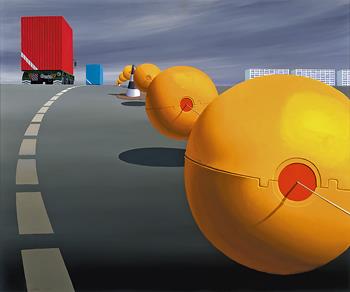

Undoubtedly one of the great paradoxes of Jeffrey Smart’s widely acclaimed legacy is that symbols of modernity, urban pressure and activity such as freeways, road signs and trucks should be imbued with an aura of stillness, order and timeless serenity more reminiscent of the Italian Quattrocento painting he so admired. For while drawing inspiration from the urban environment that has flourished in Italy since the Second World War, Smart’s immaculate compositions invariably bear no trace of the chaos or randomness of the world from which they derive. Rather, meticulously distilling his subject of the modern city down to its purely formal qualities in a manner echoing his artistic mentor Cézanne, Smart encourages his audience to see the ‘everyday’ with fresh eyes – to discern beauty in the most unprepossessing, unromantic of subjects. With its signature motif of a broad sweeping bitumen arterial seen from a low perspective and disappearing to an unknowable destination beyond, The Arezzo Turn-Off II, 1973 offers a magnificent example of the mastery and miracle of Smart’s art, encapsulating his unique ability ‘to elevate mundane familiarities… to the status of semi-mystic icons’2. Redolent with his love of ambiguity and seductive in its ‘super realism’, indeed the work is Smart at his finest, betraying strong iconographic affinities with some of the artist’s most celebrated works, including the iconic The Guiding Spheres II (Homage to Cézanne), 1979 – 80 (private collection).

The Guiding Spheres II Homage to Cezanne 1979-80 copy.jpg

Having emigrated to his adopted homeland of Italy in 1963, in early 1971 Smart acquired ‘Posticcia Nuova’, a rustic farmhouse in the heart of Tuscany, near a village called Pieve a Presciano, not far from Arezzo. Proximate to the masterpieces of Renaissance master Piero della Francesca whose passion for stillness, light and geometry famously inspired him, it was to be Smart’s home for the rest of his life. A generous financial gift bequeathed by his dear friend and fellow artist, Mic Sandford, upon his sudden tragic death only weeks earlier, subsequently enabled Smart to undertake renovation works to make the old farmhouse habitable and importantly, to transform the two-storey hayloft into two bright spacious studios, one for himself and another for his partner at the time, Melbourne surrealist artist, Ian Bent. Immersed in this delightfully idyllic ambience within the picturesque olive groves, villas and gardens of the Tuscan countryside, the first two or three years in particular at Posticcia Nuova were a period of tremendous elation for Smart. As he reminisced, ‘Life was pretty good at Posticcia Nuova... the sun poured into the loggia during winter, and went up high above us in summer, leaving the whole place cool and shaded… We would work to music. Down in his studio Ian would play records and I was treated to Mahler, and lots of Bruckner which I’d not known, as well as the three Bs – Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. It was very pleasant not knowing what music was coming next…’3

Not surprisingly perhaps, these halcyon days also heralded the emergence of some of the most compelling and commercially successful paintings of Smart’s career. Reviewing the artist’s exhibition of recent work at South Yarra Gallery in November 1972, The Age art critic Patrick McCaughey declared the group to be ‘better than he’s ever done before’, enthusiastically welcoming ‘the new access in Smart’s quality’4. Notably, the National Gallery of Victoria purchased the famous Factory and Staff, Erehwyna, 1972 from the show, while Painted Factory, Tuscany, 1972 entered the Fairfax collection. The following year when The Arezzo Turn-Off II, 1973 was unveiled at Smart’s solo exhibition at the Rudy Komon Gallery in Sydney, the display of fourteen major canvases and eight studies was similarly applauded as his most ambitious and comprehensive to date. Significantly, several paintings were acquired by public institutions and have now become some of Smart’s most well-known images, including Truck and Trailer Approaching a City, 1973 (Art Gallery of New South Wales); The Traveller, 1973 (Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art); Bus Terminus, 1973 (Art Gallery of New South Wales); Near Knossos, 1973 (South Australian College of Advanced Education, Adelaide); and The Golf Links, 1971 and Over the Hill, Bicycle Race, 1973 (both University of Sydney Art Collection, Sydney). That the paintings unveiled in this legendary show still remain universally considered among the artist’s most important is attested by the inclusion of five (including The Arezzo Turn-Off II) in the groundbreaking retrospective organised by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1999, while the aforementioned six from public institutions will feature in the forthcoming Jeffrey Smart exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia (December 2021 – May 2022).

Near Ponticino 1978 copy.jpg

Addressing the ostensible incongruity of depicting the Italian autostrada when surrounded by the beauty of the Tuscan countryside, Smart explained that the latter ‘…environment is conducive for work, and on my frequent forays to Arezzo and Florence I see a lot of that modern world which I like to paint.’5 As he elaborates further in his engaging memoir, Not Quite Straight, ‘Italy was even more beautiful seen from the autostrada – no hoardings were permitted; the only signs were those needed for the traffic and I found them beautiful, they were so well designed.’6 Although unmistakably derived from a moment glimpsed by Smart during one of his many journeys on the A1 autostrada between Rome and Florence, The Arezzo Turn-Off II does not offer a faithful depiction en plein air of an exact scene. Rather, the work here presents a composite image – constructed from the complex weaving of motifs, symbols and disparate elements recalled from either real-life locations or gleaned from other artworks, both his own and those painted by artists whom Smart admired. Accordingly, the genesis for The Arezzo Turn-Off II may be traced back to spontaneous, lucid sketches made by Smart while sitting in the front seat of his car during his travels on the autostrada, little visual notes that captured his initial sense of enchantment with the scene and would later become the aide-mémoire for his painted studies, including the gouache Sketch for The Arezzo Turn-Off II, 1973 (private collection). Subsequently embarking upon his first exploration of the subject with the full-scale canvas, The Arezzo Turn-Off I, 1973 (private collection) in which he employed a horizontal format and experimented for the first time with the technique of spray-painting to emulate the bitumen surface texture, Smart then fully resolved his compositional structure in the present work – which notably represents one of only a handful undertaken by the artist in the more dramatic vertical format. During his lifetime, Smart repeatedly avowed that his only concern was ‘putting the right shapes in the right colours in the right places’7 and indeed, in their deliberate orchestration his paintings have often persuasively been compared to the Italian films of the 1950s and 60s by Fellini, Antonioni and Pasolini which – similarly exploring the beauty of post-war Italian cities – typically feature composed shots distilled for poetic effect. Yet unlike compositions that betray a sense of evolvement, Smart’s paintings bear a remarkable quality of planned completion that is usually aided by a single dominant feature – in the present case, the broad arc of the highway arterial which literally sweeps the viewer from their low viewing point in the foreground and leads them to the dramatic horizon and mysteries of an unseen vista beyond. Such compositional doctrine in which a single element provides both the foundation and the dynamic may be discerned earlier in Smart’s oeuvre in works including Wasteland I, 1945 (private collection); Keswick Siding, 1945 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) and Approach to a City III, 1968 (private collection); and reaches its fullest dramatic expression towards the end of the seventies in Near Ponticino, 1978 (private collection) and quintessentially, The Guiding Spheres II (Homage to Cézanne), 1979 – 80 (private collection). As with these consummate later works, here the apparent simplicity of the compositional structure in The Arezzo Turn-Off II belies its overall tension and complexity, created by a series of perplexing visual conundrums.8 For example, the viewer’s perspective here is impossibly low, lower than that of a pedestrian or passenger in a car; it is broad daylight and yet the expected busy freeway is completely empty, save for the pink Lucce-branded truck disappearing over the horizon; and are we to continue along the road to Florence or take the turn-off on the right?

The Arezzo Turn-off I 1973.jpg

Like the best of Smart’s achievements, The Arezzo Turn-Off II beguiles both the eye and mind, remaining infinitely suggestive but revealing nothing. Although his works have frequently been construed as bleak commentaries on a society alienated by technology or a world impoverished by mass-produced architecture, such pessimistic interpretations would seem to negate Smart’s own professed intentions for his art. For as Barry Pearce elucidates, his paintings ‘…are, at the end of the day, expressions of himself. Container trucks which pollute cities, highways which have displaced communities, and modulised buildings which have absolved individuals from caring about each other are not in themselves beautiful. They cannot be, except that from the tranquility of his eighteenth-century farm in Tuscany, Smart has made them beautiful by extracting time and noise and pain.’9 Relentlessly asserting his faith in the timeless beauty he perceives amidst the clutter of contemporary life, Smart’s paintings convey rather, a rich sense of optimism despite their occasional uncertainties – a poignant reminder that the things which seem upon first glance to reflect a brutality to the soul can become, ironically, a source of wonder.10 As Quartermaine ultimately reiterates, ‘…Smart’s paintings are not to be looked through but looked at. If we look through them, we find only the preconceptions we brought with us – by looking at them with the attention they demand we can experience their world.’11

1. Smart cited in Capon, E., et al., Jeffrey Smart: Drawings and Studies 1942 – 2001, Australian Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2001, inside cover

2. Capon, E., ‘Still, Silent, Composed: The Art of Jeffrey Smart' in Jeffrey Smart, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1999, p.16

3. Smart, cited in Smart, J., Not Quite Straight a memoir, William Heinemann Australia, Melbourne, 1996, p. 414

4. McCaughey, P., ‘Australian Painting in Familiar Custody’, The Age, 15 November 1972, p. 2

5. Smart cited in O’Grady, D., ‘Jeffrey Smart; loitering with intent’, Sydney Morning Herald, Spectrum, 25 November 1995

6. Smart cited in Smart, 1996, op. cit., p. 386

7. Smart cited in Jeffrey Smart, 1999, op.cit., p.14

8. See Smith, G., catalogue entry for lot 16, The Arezzo Turn-Off I, 1973 in Smith and Singer, Important Australian and International Art, Sydney, 20 April 2021, p. 53

9. Pearce, B, ‘Out of Adelaide’ in Jeffrey Smart, 1999, p.32

10. Ibid.

11. Quartermaine, P., Jeffrey Smart, Gryphon Books, Melbourne, 1983, p. 78

VERONICA ANGELATOS