ARAFURA SWAMP IV, 1996

LIN ONUS

synthetic polymer paint on canvas

182.0 x 182.0 cm

signed lower right: Lin Onus

bears inscription verso: SO1 ARAFURA SWAMP IV

Private collection, Victoria, acquired directly from the artist in 1996

Arafura Swamp, 1990, synthetic polymer paint on linen, 182.0 x 182.0 cm, in the Baillieu Myer collection of the 1980s, illus. in Neale, M., Urban Dingo: The Art and Life of Lin Onus 1948 – 1996, Craftsman House, Sydney, 2000, p. 77

Screenshot 2025-03-04 134344.jpg

Lin Onus’ technically polished and stylistically hybrid Postmodern paintings sought to reconcile the various facets of his own cultural métissage, as a metaphor for broader political and social reconciliation, and through his art illuminate the underlying indigenous cultures of the Australian continent. A lightning rod moment came for the artist following a pivotal meeting with Yolŋu elders in Maningrida, Arnhem Land in 1986: ‘It suddenly hit me that you could paint both what you saw and what lay underneath it – what is understood – as well’, he explained in 1991.1

Thus, with a dazzling mosaic of layered representations, Onus’ immersive Arafura Swamp IV, 1996 simultaneously presents two opposing landscape views of a site of great indigenous cultural significance, Gurruwiling, the Arafura Swamp wetlands of central Arnhem Land. Incorporating in a unified vision many of his most powerful and striking stylistic devices, this painting belongs to a celebrated series of works stemming from a large work of the same name, Arafura Swamp, 1990 (Baillieu Myer Collection, Melbourne), a masterpiece of his jigsaw motif. The Yorta Yorta artist, a largely self-taught pioneer of Koori activist art, was at the height of his powers in 1996, working with Margo Neale on a large retrospective exhibition at the University of Queensland Art Museum when he suddenly passed away, at the age of 47.

Painted at the liminal hour of dusk, the sublime surface of Onus’ billabong, dotted with blooming pink water lily plants is still. Drawing on the artistic lineage of H. J. Johnstone’s Evening Shadows, Backwater of the Murray, South Australia, 1880 (Art Gallery of South Australia), the water reflects the rhythmic, graphic black trunks of native gums, its glassy transparency revealing a bed of russet leaflitter at the bottom of the canvas. Punctured unevenly with rectangular apertures placed throughout the painted surface, Onus has compromised the integrity of this view. Revealed through these interstices is the same landscape painted in colours mimicking bark and natural earth pigments, borrowing the graphic flatness and ceremonial rarrk cross-hatched motifs of local Yolŋu bark painting, whose sacredness Onus had recently been granted the authority to paint.

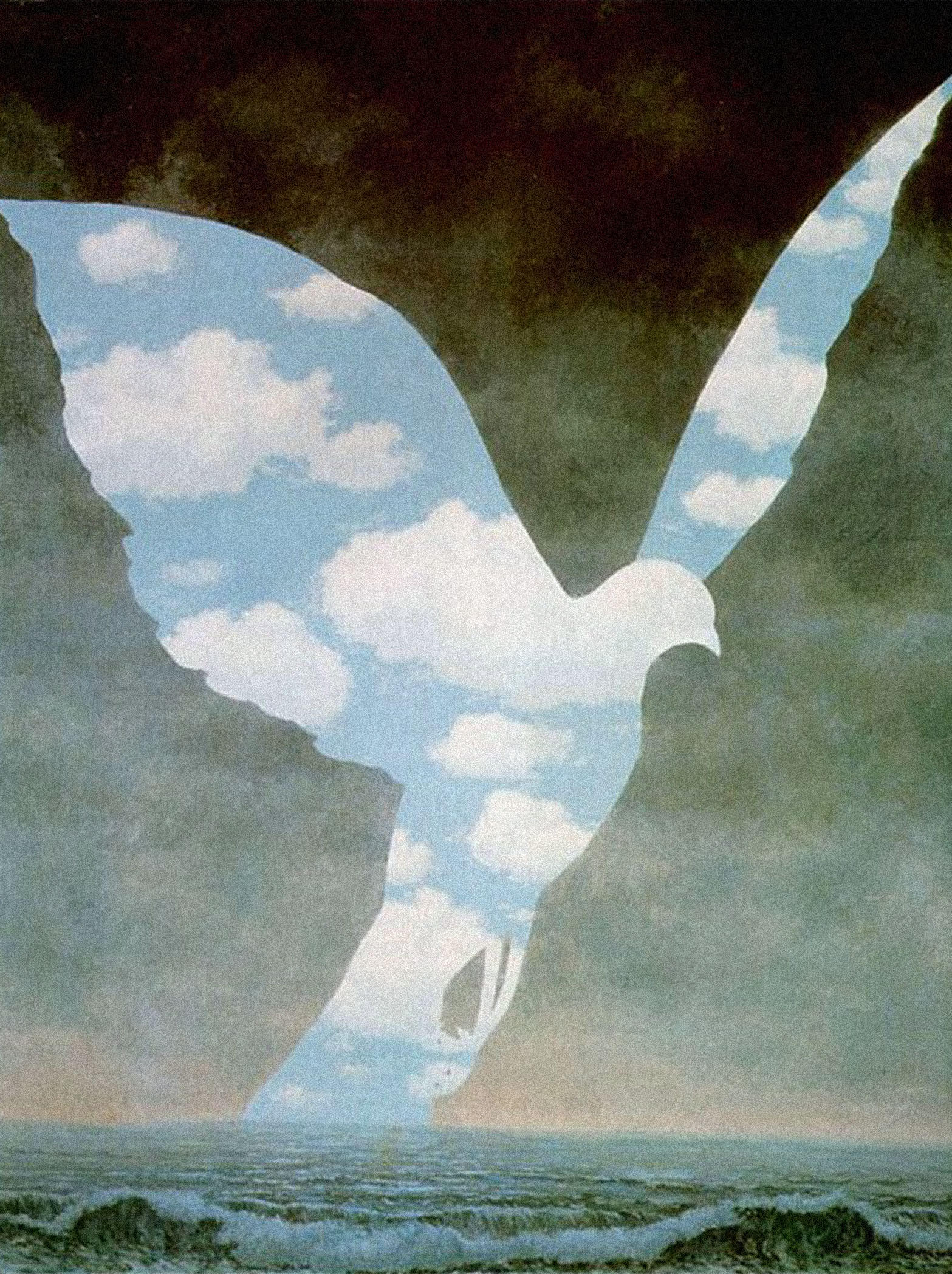

220988 Magritte The Large Family.jpg

A self-proclaimed ‘cultural mechanic’2 and post-modern bricoleur, Onus found in the works of Belgian surrealist René Magritte, an artist whom he admired3, a visual deceit that he could use to illustrate explicit themes of Indigenous cultural dislocation: the treacherous double image and fragmentation using a jigsaw motif (see for example, René Magritte, The Large Family, 1963). Onus’ metaphorical dislocations disrupt and subvert assumptions on ideologies of representation and the implications of belonging and custodianship they project. The first of these works arose in the 1980s around questions of land rights and restoring cultural knowledge in the wake of destructive colonial assimilationist policies, for example, the painting Picking up the Pieces, 1986 and linocut Dislocation, 1986. Arafura Swamp IV joins a small and important group of double-image landscape paintings arising from these early works, featuring overlays and/or perforations.4

The incorporation of dual perspectives in his artworks became Onus’ picturesque and gently humorous strategy to surmount prejudiced notions of what aboriginal art could and should look like. Self-consciously, they interrogate the process of representation itself and provide an unwavering reminder that this land is, and always has been, Aboriginal land. Originally, these fractured and spliced works referred to ‘a number of my friends who are trying to find out where they have come from, and I suppose, where they are going’, the artist elucidated in 1990.5 This search for belonging and land custodianship became more poignantly personal for the artist towards the end of his life, as he discovered his ancestry was descended from Yorta Yorta nations, and not Wiradjuri as he originally had been led to believe.6

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Lin Onus painted landscapes of his local environs around the Dandenong Ranges in a Western photorealist style, influenced by the works of older, Indigenous artists who had been successful in using a European landscape tradition to depict their ancestral lands: Ronald Bull (1942 – 1979), Revel Cooper (c.1934 – 1983), and Albert Namatjira (1902 – 1959), all of whom had visited the Onus family in Melbourne. It was Onus’ later involvement with the Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australia Council, however, that provided a transformative visit to Maningrida, NT in 1986 – a ‘spiritual awakening’ during which he met Senior Yolŋu artist, Djiwul (Jack) Wunuwun, whose ancestral lands run along the Northern edge of the Arafura Swamp, which is depicted in this painting. Over the course of dozens of subsequent pilgrimages to visit Wunuwun, Onus was adopted by and welcomed into the Murrungun-Djnang clan, initiated into cultural knowledge systems and given permission to use sacred rarrk designs and storylines. Wunuwun’s philosophy of ‘seeing below the surface’ and using artistic hybridity to achieve reconciliation was also shared and adopted by Onus, explored in depth in these late water-and-reflection paintings.7

Occupying what anthropologist Levi Strauss defines as that ‘in-between’ space between multiple worlds, the densely layered patterning of Arafura Swamp IV oscillates between two interwoven modes of viewing and systems of understanding the world, metaphorically portraying Indigenous displacement and erasure. Like the foundational Arafura Swamp, 1990, the revelation of an underlying bark design gives primacy to its ancient origins.8 The directional lines of black tree trunks and the discs of lily pads unify the two images, indicating that in the impossibility of returning to a land of pre-colonisation, the co-existence of multiple and equivalent frames of reference is a sustainable path to progress.

1. Onus, cited in Moore, F., ‘Cultures find a common cause’, Australian Financial Review, Sydney, 15 March 1991

2. Neale, M., Lin Onus, Savill Galleries, Melbourne, 2003, p. 1

3. Neale, M., Urban Dingo – the Art and Life of Lin Onus 1948 – 1996, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2000, p. 15

4. These include Jimmy’s Billabong, 1988 (National Gallery of Australia) overlaid with rarrk; Arafura Swamp, 1990 (Baillieu Myer Collection, Melbourne) with square cut-outs revealing an underlying bark painting; and Barmah Forest, 1994 (Australian Heritage Commission, Canberra) with mismatched jigsaw piece cut-outs.

5. ‘Lin Onus. Language and Lasers’, Art Monthly Supplement, no. 20, May 1990, p. 19

6. Letter, dated 14 July 1995, from Lin Onus to Art Gallery of New South Wales, AGNSW archives

7. Davis, P., ‘In Touch with an artist’s Aboriginality’, Canberra Times, 7 July 1990, p. 21 and Mundine, D., ‘Jack Wunuwun’, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia Handbook at: https://www.mca.com.au/collection/artists/jack-wunuwun/ (accessed March 2024)

8. Neale, op. cit., p. 16

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH