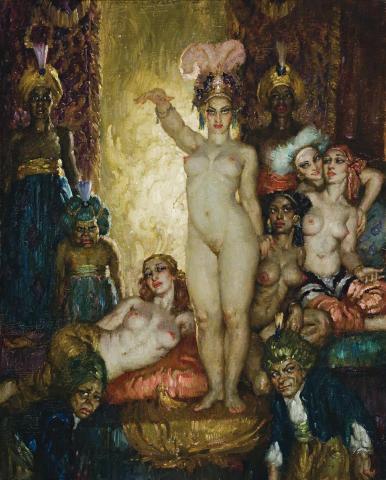

INCANTATION, 1940

Norman Lindsay

oil on canvas

76.0 x 61.0 cm

signed and dated upper centre: NORMAN LINDSAY 1940

Sotheby's, Melbourne, 6 April 1987, lot 113

Gould Galleries, Melbourne

Private collection, Melbourne

Deutscher~Menzies, Sydney, 18 March 2008, lot 40

Company collection, Melbourne

Bloomfield, L., Norman Lindsay Oil Paintings 1889 – 1969, Odana Editions, Bungendore, 2006, pp. 236–237 (illus.)

Norman Lindsay in his autobiography declared that 'the feminine image was the central motif of my work' adding that his wife Rose 'dramatized it for me in the flesh under terms which involved me in all its emotional complexities, lyrical and demonical.'1 His mention of the combination of lyrical and demonical is significant not only for Incantation, but much of Lindsay's art generally. For Lindsay, the seductive powers of women possess men both through their sublime beauty and the enthrallment of their sexual appeal. As in life, they are dominant in his art, the figurative pivot around which his compositions revolve. The Junoesque model for Incantation was the fair-haired Rose. Bold in form, firm of breasts, and accommodating of thighs. The principal female figure in Norman Lindsay's paintings and etching invariably represents his ideal of womanhood. She can be found in like form in two earlier etchings, Enter the Magicians 1927 and The Little Witch 1937, developed in Incantation into the full blown image of the all powerful and dominant woman, exotically and erotically beautiful.

The link to witchcraft in the title, the calling up of the magical spell to bewitch, is given form through alluring flesh, pose and gesture. Commanding in her triumphant frontalism and powerful look, her eyes bore directly and hypnotically into those of the viewer. Interestingly, the gesture of her right arm and hand in particular, and the pose in general bare a similarity to that of Bertram Mackennal's once highly controversial bronze Circe of 1893. This is no accident, for Paris in the late nineteenth century was under the spell of Symbolism and its fascination with the femme fatale found in the works of Oscar Wilde, the performances of Sarah Bernhardt, and the paintings of Gustave Moreau and Rupert Bunny. Circe was the witch-love-goddess without equal of ancient Greek times, turning Ulysses' men into swine and then ensnaring in her arms the Greek super hero for a year of amour. Lindsay's lady also speaks of Venus the love goddess of classical Rome, plumed in splendour. Dramatically lit from behind, Lindsay presents all with great theatrical effect, the surrounding beauties, turbaned attendants of guardian Nubian slaves and gnomes all observing with fixed attention the effect of her wizardry. In Lindsay's world of art women are supreme through their ability to enslave the mere male.

1. Lindsay, N., My Mask, An Autobiography, Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1970, p. 176

DAVID THOMAS