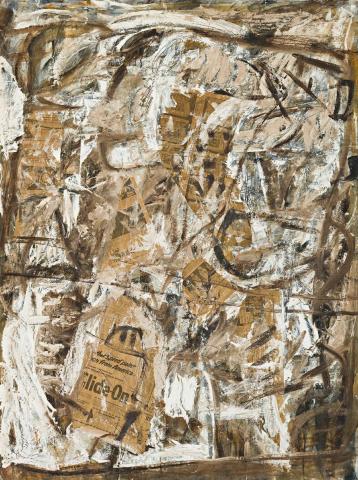

ABSTRACT ON HARDBOARD NO.2 (TP215), c.1959

Tony Tuckson

oil, pencil, newspaper collage on composition board

122.0 x 91.5 cm

David Bluford Collection, Sydney

Private collection, Queensland

Thomas, D., Free, R. and Legge, G., Tony Tuckson, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1989, pp. 181, 79, pl. 72 (illus.)

Although Tuckson had exhibited the occasional painting in annual Sydney exhibitions during the early years of his career, it was not until 1970 that he held his first solo show, and 1973, his second - only months before his untimely death at the age of 52. As the Deputy Director and unofficial curator of Aboriginal and Melanesian art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales for nearly two decades, Tuckson was acutely aware of the conflict of interest involved with publicly pursuing his own art practice while holding an administrative position at the Gallery, and accordingly, his dedication to art always remained a very private vocation. Notwithstanding, Tuckson's 1973 exhibition was met with such extraordinary enthusiasm and success that art critics and journalists soon extolled him the 'undiscovered master' of Australian abstraction.

Betraying a myriad of artistic influences from Turner, Picasso, and Klee to fellow Australian painter Ian Fairweather, Tuckson's oeuvre is rich in its diversity, encompassing many different painterly approaches and phases. Immediately following his large-scale pure action paintings executed in the vein of Pollock, Abstract on Hardboard No.2 belongs to a group of abstract works dating vaguely from 1959 which feature a mixed-media technique juxtaposing collaged newspaper fragments alongside delicate, graffiti-like lines and forms, all rendered in a subdued, earthy palette. Offering a stark contrast to his preceding achievements, the shift in scale and detail here directly reflects Tuckson's deepening involvement with Aboriginal art towards the end of the decade - including his first-hand observation of minute sensitivity in the making of bark paintings at Yirrkala in 1959, and his close friendship with the great exponent of that community, Mawalan. Indeed, in seeking to change prevailing attitudes at the time, in 1956 Tuckson had laid the foundations for the earliest public collection of Aboriginal art to be acquired for its aesthetic rather than ethnographic value, and in 1960, prepared the first major exhibition of Aboriginal art for tour around the country. As Jenny Isaacs notes, 'He alone, of all major state gallery officials, had responded to Aboriginal Art from the perspective of an artist... He respected individual Aboriginal artists and their intentions with regard to their work and collected numerous 'myths', realising the importance of religious meaning to the artists.'1

With its highly personal and expressive language of signs articulated through the written mark and textural layering, thus the present composition affords valuable insight into the artist's lifelong preoccupation with the very act of painting itself; as James Gleeson reflects, '... His pictures are about what it feels like to paint a picture - and as Tuckson feels it, a large part of it is agony. Making a picture or indeed any kind of art is a kind of birth. There is labour involved... Tuckson isn't interested in the art that conceals effort. He shows the making of a painting with all the travail fully exposed, without prettification or pretence that it hasn't hurt... In the end he triumphs because he does communicate his urgency through the painting. The pictures become a point of contact. The viewer who takes the risk of opening himself to these works will be rewarded by a rare glimpse of the emotional and physical costs of creativity.'2

1. Thomas, D. et al., Tony Tuckson, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1989, p. 17

2. Gleeson, J., 'The Travail of Painting', Sun-Herald , 22 April 1973

VERONICA ANGELATOS